Ancient 'British' rock fish trap dating to approx. 1000

.

Over the last two days I’ve had the good fortune to listen to Dr. Charles Menzies () speak in Prince George on two different topics – yet intimately related…

On the UBC website it lists Charles research interests as such:

My primary research interests are the production of anthropological films, natural resource management (primarily fisheries related), political economy, contemporary First Nations’ issues, maritime anthropology and the archaeology of north coast BC.

I have conducted field research in, and have produced films concerning, north coastal BC, Canada (including archaeological research); Brittany, France; and Donegal, Ireland.

Last night, at Art Space within Prince George’s independent book store Books & Company, Menzies delivered a presentation called:

“Abalone, Pipelines, and Aboriginal Rights – Making Sense of Coastal Opposition to the Northern Gateway Project.“

Found it to be quite a fascinating subject, quite enjoyed Menzies taking some pointed shots at academia and some ‘status-quo’ theories of some academics. Stirring the pot a little… (wooden spoon anyone?)

Namely, taking shots at some archaeologists that have adopted some rather faulty views of what folks on the coast may, or may not have been doing pre-contact.

You know at the apparent “discovery” of North America… and especially coastal northwestern North America.

In the research that informed Menzies’ presentation he visited ancient (and contemporary) Gitxaała village sites.

Gitxaała (Kitkatla) territory is south down the coast from Prince Rupert, BC and in the general vicinity south of the Skeena River mouth. As I understand it, Dr. Menzies’ family comes from that area, and he himself grew up in Prince Rupert.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

He explained that his research was quite purposely directed to do some investigation of community-known ancient village sites (and still contemporary used areas) which are along the proposed Enbridge oil super-tanker route, which would be used if Enbridge and Harper get their way in ramming a TarSands oil pipeline (Northern Exit-way) down the throats of north-central, north-coastal BC people’s throat.

(that last bit being my editorializing…).

He explained that the ‘status-quo’ archaeological ‘investigations’ and theories of this particular area suggest that people of this area did not harvest many abalone.

Community members most clearly say otherwise…

But archaeological theory continued to deny otherwise… look at our evidence, they say…

good old: ‘absence of evidence must be evidence of absence’…

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Dr. Menzies and his crew, through low impact archaeological investigation and community elder direction to sites, sort of blew that proverbial misguided boat out of the water.

Or… i suppose… put the bilhaa (abalone) back in the water… one might say…

Menzies’ and crew found, what one might characterize, as no shortage of evidence of abalone use by ancients. Some dating back further than 4,000 years.

Menzies has an interesting paper at his documenting the ancient Gitxaała connection to abalone — bilhaa.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

There’s a fitting quote early in the paper, which also relates to recent posts on this site regarding the federal government’s apparent ‘modernization of Canada’s commercial fisheries’:

Menzies suggests:

The development of the non-aboriginal commercial dive fishery in British Columbia is a classic example of competitive greed combining with ineffectual resource management to decimate a resource.

The story of the collapse of abalone (bilhaa ) up and down the coast, is a common story, caught quite well by Menzies:

Bilhaa is one of a set of Gitxaała cultural keystone species. Cultural keystone species are species that “play a unique role in shaping and characterizing the identity of the people who rely on them.

These are species that become embedded in a people’s cultural traditions and narratives, their ceremonies, dances, songs, and discourse”. Until the late 20th century, Gitxaała people were unhindered in the harvesting of bilhaa within the traditional territory and in accord with longstanding systems of indigenous authority and jurisdiction.

However, the rapid expansion of a non-aboriginal commercial dive fishery through the 1970s-1980s brought bilhaa stocks perilously close to extinction. The DFO responded to this non-aboriginal induced crisis by closing the total bilhaa fishery. DFO made no apparent effort to accommodate indigenous interests.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Abalone (bilhaa), was most certainly not just limited to the BC coast.

In a recent research project I’ve been involved in… here is an image from old journals (e.g. namesake for Moricetown, Morice Lake, etc.) from Dakelh (Carrier) people in the now Ft. St. James area in late 1800s.

abalone ornament from Dakelh people of BC interior

These types of ornaments would have traveled in on the oolichan grease trails and other various trade routes including dentalia shells, and other items, with prized hides of various sorts and soapberry traveling to the coast.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

In today’s presentation at UNBC Charles spoke about his research into artisanal fisheries on the coast of France — in other words small family, or community owned fisheries…

…and the impact of globalization on these fisheries and fisherfolks.

The story is remarkably similar to the story of agriculture throughout Canada, and other areas. The move from family-owned plots of land and specialized crops, to monoculture, highly centralized and controlled institutions and corporations that control much of the flow.

As Menzies suggested, when fish prices change in Brazil it affects fisherfolks in Canada… the impact of globalization (and maybe one might suggest: ‘systems theory’…)

Similar with wheat, barley, rye, and so on…

The fish market of the globe is largely controlled by only a handful of organizations. Fishing gear is largely down to only two or three companies.

Gee, does this sound like Monsanto or other mega multinational corporations controlling agriculture worldwide…?

The benefits of this, largely benefiting only a few, and the implications and drawbacks having devastating consequences on the small players of the world — you know… the little players like community members and families.

… those same “families” that all politicians seem to be soooo concerned about…

…from BC’s current un-elected premier Clark to the highest fed levels in Canada and even current Republican blather flooding Canadian airways these days as they try and select a presidential candidate.

(gee… one might almost feel bad for all those “singles” out there… hey?)

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

The great thing about sitting at the ‘back’ during presentations such as Dr. Menzies’ is that one can watch the various academics squirm and frown with mere mention of ideas that might challenge the status-quo economic theories or otherwise that are currently being jammed down the whole medley of ‘students’ out there.

All the more sad as they riddle themselves with debt (students that is) the size of a small European nation and learning tired and worn out theories — such as the “invisible hand of the market” and other ‘strength of privatization’-bumpf flying around like the old passenger pigeon of old

(or running around like a dodo bird with its head cut off).

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

Not unlike the current Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ bumpf-filled, fluffy, blather around ‘modernizing’ Canada’s fisheries.

(yeah, sure… go for it… modernize the ‘fishery’… but I think i can safely say that the fish themselves are not all that interested in ‘modernizing’…

… think it’s called barely surviving…

…fish populations around the world are on death-row, which means the fleet can be as modern as it wants to be, but an empty fish net, is an empty fish net…

…even if it’s the latest carbon-fiber, titanium-lined, indestructible twine net, with GPS-spotter plane, fuel efficient, carbon credit, carbon neutral, double-hulled, long-distance trawl, Marine Stewardship Council-certified, boat and fairly-paid, union-represented crew.

.

empty is empty…

(net… river… ocean… shoreline that once had abalone…)

or we… simply… just keep fishing down the food chain until bullheads start looking pretty tasty at the latest and greatest restaurants…

_ _ _ _ _ _

Great finish to this, from Menzies (and colleague Caroline Butler) paper: “Returning to Selective Fishing through Indigenous Fisheries Knowledge”:

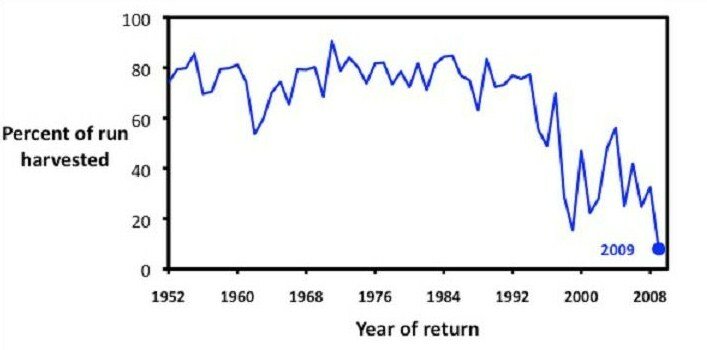

The historical abundance of salmon along the west coast of North America has been significantly reduced during the last two centuries of industrial harvest. Commercial fisheries from California to Alaska and points in between have faced clearly documented restrictions on fishing effort and collapse of specific salmon runs.

Even while salmon runs on some large river systems remain (i.e., the Fraser and Skeena rivers), many smaller runs have all but disappeared. The life histories of many twentieth-century fisheries have been depressingly similar: initial coexistence with indigenous fisheries; emergence of large-scale industrial expansion followed by resource collapse; introduction of limited restrictions on fishing effort, which become increasingly severe, making it hard for fishing communities to survive and to reproduce themselves.

Yet for nearly two millennia prior to the industrial extraction of salmon, indigenous peoples maintained active harvests of salmon, which are estimated to have been at or near median industrial harvests during the twentieth century.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

Menzies raised this point in the discussion part of his presentation today at UNBC.

It’s one of my favorite points, which I’ve used in many presentations over the years.

In simple terms…

…the level of pre-contact salmon fisheries is estimated to actually be higher than the average annual industrial harvest of salmon over the last century.

Wow, I think I felt the flinch in the room today from a few academics…

And then the excuses and questions and qualifiers start flying when some folks realize that the pedestal that academic keeps trying to stand on is jussssst a little bit shaky.

Maybe not even shaky… it’s simply an imagined pedestal.

Just picture the classic Wiley Coyote running off the cliff chasing Road Runner then realizing there’s nothing under him…

Menzies and Butler conclude their paper on selective harvesting:

Scant attention has been paid to traditional fishing techniques and technologies and the ways in which they might contribute to sustainable harvesting and species conservation, and indeed, provide an alternative to current practices.

Traditional knowledge of salmon production may be of significant value in the current search for successful selective fishing techniques for the British Columbian salmon fisheries.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

See that anywhere in DFO’s plans…?

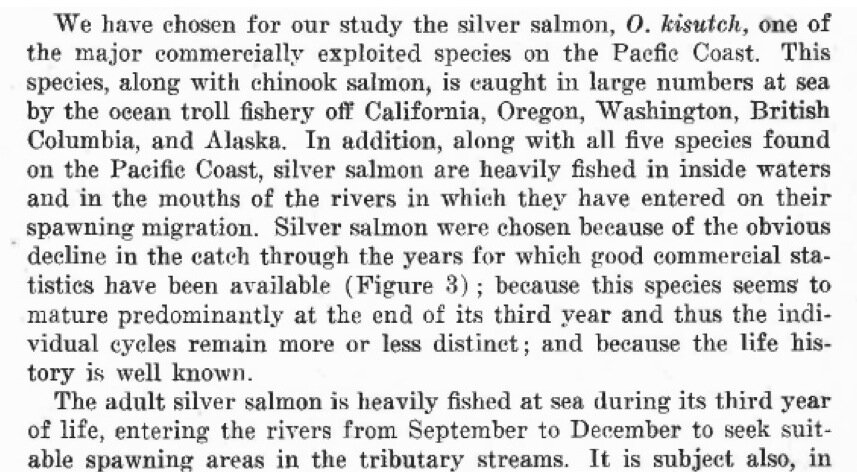

The image at the beginning of this post is from a British newspaper story:

For a millennium it has lain undisturbed beneath the waves a stone’s throw from one of Britain’s best-loved beaches.

But now modern technology has revealed this ancient fish trap, used at the time of the Norman Conquest.

Stretching more than 280 yards along the sea bed, the V-shaped structure was used to catch fish without the need for a boat or rod. Scientists believe it is one of the biggest of its kind. [Menzies might argue this as he’s found kilometres of these along the northwest BC coast]

The trap close to Poppit Sands on the Teifi Estuary in Dyfed was discovered by archaeologists studying aerial photographs of the West Wales coast. [love that term “discovered”]

It was designed to act like a rock pool, trapping fish behind its stone walls as the tide flowed out.

At its point is a gap where fisherman would have placed nets to catch fish. They could also have blocked up the gap, and then scooped up fish trapped in the shallows.

ancient British fish trap

What a concept… so my ancestors in Wales and other areas were using similar selective fishing community-based technology… hmmm.

Pop this into the old search engine ‘ancient rock fish traps’ and you will find examples from around the world: the Arctic, Australia, Hawaii, Indonesia, Mediterranean, and so on…

What a concept, local knowledge being put to use to ‘manage’ a local resource. (and ensuring that resource survives for many human generations…)

I think they call that ‘rocket science’… or is it ‘not’…

science that is… it’s just knowledge… and… ummmm… COMMON SENSE.