Pacific salmon range

Many can ponder the “F”… however in this case it’s for the old standard “Fail”. As in the Department of Failing Objectives. Or Disappearing Fish in the Oceans… Or Denial Forever-On…

Jest aside; one of my hopes as I started this website and blog was to try and hilight positives; tell good stories; maybe add some humor to some dismal stories (ghad knows we have enough negative media, lowest common denominator television, and ranting blogs…). I thought maybe I’d run along the fringes of some new ideas, new approaches, maybe laud new bureaucratic systems to looking after natural resources.

And, maybe — just maybe — tell a positive story that could be etched in some annal of my life; that I could tell my (currently) three young kids.

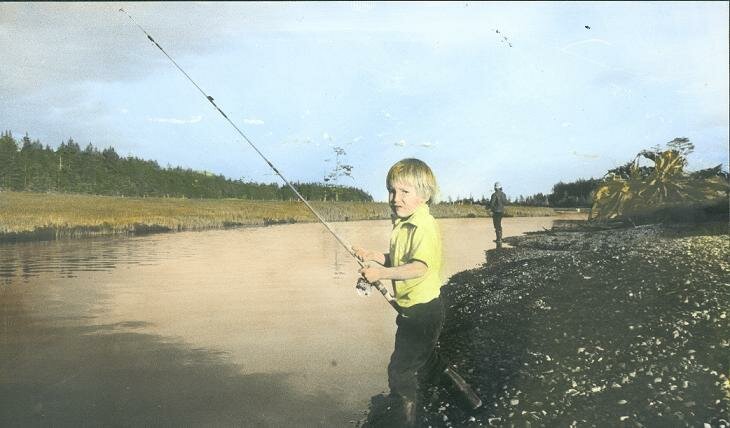

When I was about four — same age as my daughter now I spent a lot of time on the river fishing. A lot…

Right on the very gravel bar, almost in the very spot I’m standing in the picture above — I caught my first coho. A memory imprinted on my brain.

As one older and wiser reading this blog, you could imagine that with three young kids, I’m not that old. And yet, my memory of coho returns is quite vivid. Not the: “walk on their backs across the river”- type memories — however, still substantial runs that presented a kid growing up — with no shortage of thrills.

These days… not quite. The chances of my kids hauling in a 20+ pound coho from a dark, murky, slow-moving, river?

Slim.

For me… I don’t see it as rocket science. The causes of salmon declines along the Pacific Coast of North America are not difficult to pinpoint.

- One — look in a mirror.

- Two — look at and feel our rivers.

- Three — look upstream.

So when I read a letter released today by DFO (Fisheries and Oceans Canada) titled:

Management Measures for Fraser River Spring Chinook

that suggests we will “protect and conserve Spring 42 Chinook” by going fishing:

The intention of this objective is to substantially reduce fishery exploitation rates to effectively protect and conserve Spring 42 Chinook.

…I can see that the demands of folks today are sacrificing what folks of my kids generation will require. The demands of today will continue to reduce opportunities for the future — especially when it comes to wild salmon.

The sport fishery in Juan de Fuca, and other areas, will remain open with a limit of two Chinook per day (with size restrictions demonstrated to be ineffective). Some commercial troll fisheries will close; however some along west coast Vancouver Island will be open with restrictions. And at the mouth of the Fraser — catch-and-release sport fisheries (exactly what First Nations have repeatedly asked not to allow).

And if you saw yesterday’s post — the Chinook “whopsee factor” — DFO failed miserably on reducing exploitation last year as outlined in their “management plans”. Exploitation actually grew from years previous. This “whoopsee” factors is OK when you spill milk (you know, the don’t cry over… part); Not so good when you’re responsible for looking after salmon populations in a death spiral.

And here’s the part that always floor me…:

In addition to the proposed fishery management actions for 2010, the Department recognizes that there are likely significant extenuating factors, including the effects of climate change on salmon ecosystems, which may be affecting the survival of southern BC chinook.

“There are likely”…? Come on Ms. Farlinger (Regional Director of Fisheries and Aquaculture DFO Pacific) and author of the letter.

As my kids say: “oh mannnn….”

I’m guessing that maybe Ms. Farlinger – or here Chief letter writer didn’t check into the actual meaning of “extenuating”… One online dictionary suggests:

“serving or tending to reduce the severity of guilt or blameworthiness; as, extenuating circumstances.”

So, who’s feeling they need to reduce the severity of guilt or blameworthiness?

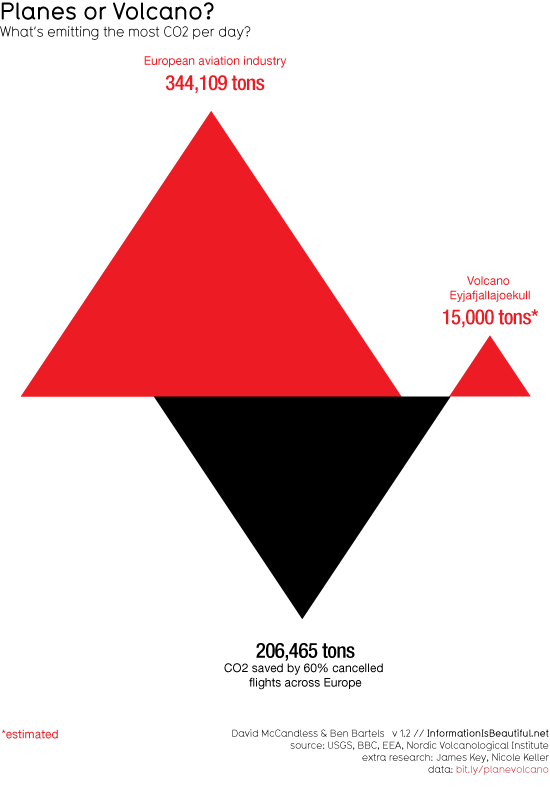

With the current governing party, I’m not holding my CO2 – laden breath. Not only will salmon need as much diversity as possible in coming years as river temperatures increase. However, as Conservative MP wrote in a Montreal paper last month:

In a letter this month to Montreal’s La Presse newspaper, Conservative MP Maxime Bernier expressed skepticism that human activity even is the leading cause of warming.

“What is certain,” he wrote, “is that it would be irresponsible to spend billions of dollars and to impose unnecessarily stringent regulations to solve a problem whose gravity we still are not certain about.”

Irresponsible… indeed.

I can hear it right now…wait for it: “oh mannn….”

I am taking faith though, in one of the most bureaucratic bafflegab (a.k.a. ) laden paragraphs I’ve read… well… since I was on DFO’s website… yesterday:

The Department is working on a comprehensive, multi-faceted management framework for conserving southern BC chinook conservation units, including Fraser Spring 42 chinook, which addresses harvest, habitat, enhancement and research priorities over the long term.

If you haven’t read my … the Wild Salmon Policy is now becoming a teenager; it was born in the late 1990s. And if there’s one thing I know from many years of coaching sport and contracts as a youth worker… I don’t tell teenagers about my “comprehensive, multi-faceted management framework” for dealing with their hormonal imbalances, clutziness, and general raging attraction towards members of the opposite sex.

It’s much easier to… just do shit.

I’m already tired of my DFO-absurdity rants… I think I’m going to have to go in search of new salmon topics. Unfortunately, when it comes to folks trying to do what’s best for wild salmon, it’s hard to escape that big giant bureaucratic silo that is supposed to be conserving wild salmon as it’s number one priority… and engaging in ecosystem-based planning.

Next week I am driving to Portland, Oregon for a multi-day international conference: — hosted by the . Maybe there will be some interesting stories there?

Maybe I’ll hear stories of folks making hard choices now, to ensure things like healthy salmon runs for the next generation?