One fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish…

There’s some wisdom in this great old rhyme. And for some reason it is also a very popular search term to find this website which leads folks to this post from last year — . (Whether folks stick around or not is another story…)

As mentioned in that post:

I haven’t seen the book in awhile; however, I don’t think there were any rhymes about “mark-recapture” sonar hydroacoustical split-beam single-beam DIDSON data capturing salmon counting wonder tools.

See if Suess’ fish on the right were captured by one of these techno-gizmos utilized for counting salmon they’d show up as some grainy fuzzy blob resembling a baby ultrasound image.

See that silver streak in the image on the right… that’s a sockeye… red and green fish… can’t you tell?

If you go to this site () you can watch a little movie of this blip going by.

That paper also explains: Why would a fish biologist use an imaging sonar system to count fish?:

…Fisheries managers first allocate a portion of returning sockeye salmon to meet annual escapement goals (the number of fish returning to their home stream to spawn to sustain each stock) and then the remaining fish are allocated to harvesting by First Nations, commercial and recreational fisheries.

Reliable escapement data is a key requirement for effective management of sockeye salmon. Historically, the escapement of sockeye salmon stocks for which pre-season forecasts predict more than 25,000 fish will be returning is measured using a mark-recapture program (MRP).

These programs involve capturing and marking returning salmon below their spawning grounds and then constant monitoring of the spawning grounds to determine the ratio of marked to unmarked fish. Knowing the ratio of marked to unmarked fish recaptured and the total number of fish that were marked downstream, the number of fish that return can be estimated.

As a result of stock-rebuilding efforts that were initiated in 1987, the number of stocks exceeding the 25,000 fish criterion (changed to 75,000 fish in 2004) has increased, placing considerable pressure on the resources available for assessing sockeye salmon stocks in the Fraser River. A mark-recapture estimate requires a large field crew and since sockeye salmon begin returning to their streams in July and may not finish spawning until late November or early December, these programs are both labour-intensive and costly to operate. [my emphasis]

_ _ _ _ _

Hmmm. So let’s recap:

Reliable data is a key requirement of effective management… mark recapture studies are labour intensive… we are still “estimating” regardless of method… AND we have changed the threshold of what runs are considered important enough to try and enumerate — it was 25,000 but now it’s 75,000.

Does this then mean that we are only concerned about the larger runs and are focusing less and less on the smaller runs — those smaller runs which are the key components of biodiversity?

And… now our data is actually less reliable because between 1987 and 2004 we were trying to collect data on all runs larger than 25,000. After 2004, it’s now only runs greater than 75,000.

What happened to all of those runs that were less than 25,000? And all the runs that are between 25,001 and 74,999?

And what’s going to happen to runs that were greater than 75,000 after 2004, but have now dwindled to less than 75,000 — do we stop counting?

What happens, for example, if all the Fraser sockeye runs become less than 75,000? Do we stop enumerating?

At that point, the status-quo measurement of ‘economic values’ of the sockeye fishery would be next to nil — and so why would a Department of “Fisheries” and Oceans be concerned about these fish if there were limited “fisheries” focusing on them?

Say for example… like North Atlantic Cod… what is the comparison of resources spent on enumerating and counting cod stocks when there were intensive industrial fisheries — as compared to now after they were “managed” into oblivion?

_ _ _ _ _ _

One of the main questions I might ask here is: WHY?

For data to be “reliable” it needs to be collected in some form of similarity or compatibility… doesn’t it?

As one meaning of “reliable” suggests: “Yielding the same or compatible results in different clinical experiments or statistical trials.”

_ _ _ _ _

In the same paper, the authors suggest:

What are we doing? We are investigating the dual-frequency identification sonar (DIDSON) technology as alternative method for counting fish in sockeye salmon stocks that are assessed with mark-recapture programs, i.e., large returning stocks. Sonar is a non-invasive, non-destructive technique for monitoring the abundance of fish populations and this is an important advantage given the high esteem for sockeye salmon in British Columbia.

And so… as stated, the DIDSON technology is meant to replace those pesky labour-intensive mark-recapture programs — on large returning stocks.

So what are we doing for the small stocks — vital to biodiversity, and bears, and birds, and bees, and so on?

As the article points out… there are only a few rivers on the entire Fraser (of the 150 or so in the Fraser that support sockeye) that are conducive to utilizing DIDSON technology.

Based on a combination of in-stream testing and site visits in 2004, we found that the physical characteristics and fish behaviour at 9 sites on 6 rivers in the Fraser River watershed permitted effective use of the DIDSON system for counting sockeye salmon…

…We identified six river systems in the Fraser River on which the DIDSON imaging system can be effectively used to count returning adult salmon. All six rivers (Chilko, Horsefly, Mitchell, Scotch, Seymour and the lower Adams River) support large and important sockeye salmon stocks.

_ _ _ _ _ _

This isn’t to take away from the potential value of utilizing technology like DIDSON in some systems… the fundamental problem here is this automatic focus on “large and important” stocks.

Who is making these assessments on what stocks are “important”?

And based on what criteria?

“Large and important” seems to automatically assume that stocks which are the focus of commercial fisheries — are the “important” ones; simply because they are “large” runs.

_ _ _ _ _ _

What is the fundamental conclusion of the paper?

Using the DIDSON system to estimate the escapement of some of the major sockeye salmon stocks in the Fraser River is likely to improve data quality in terms of its accuracy and precision and this improvement may be achieved at lower cost to existing stock assessment programs because the labour and operating costs of a DIDSON system are lower than similar costs for a mark-recapture study on the same stock.

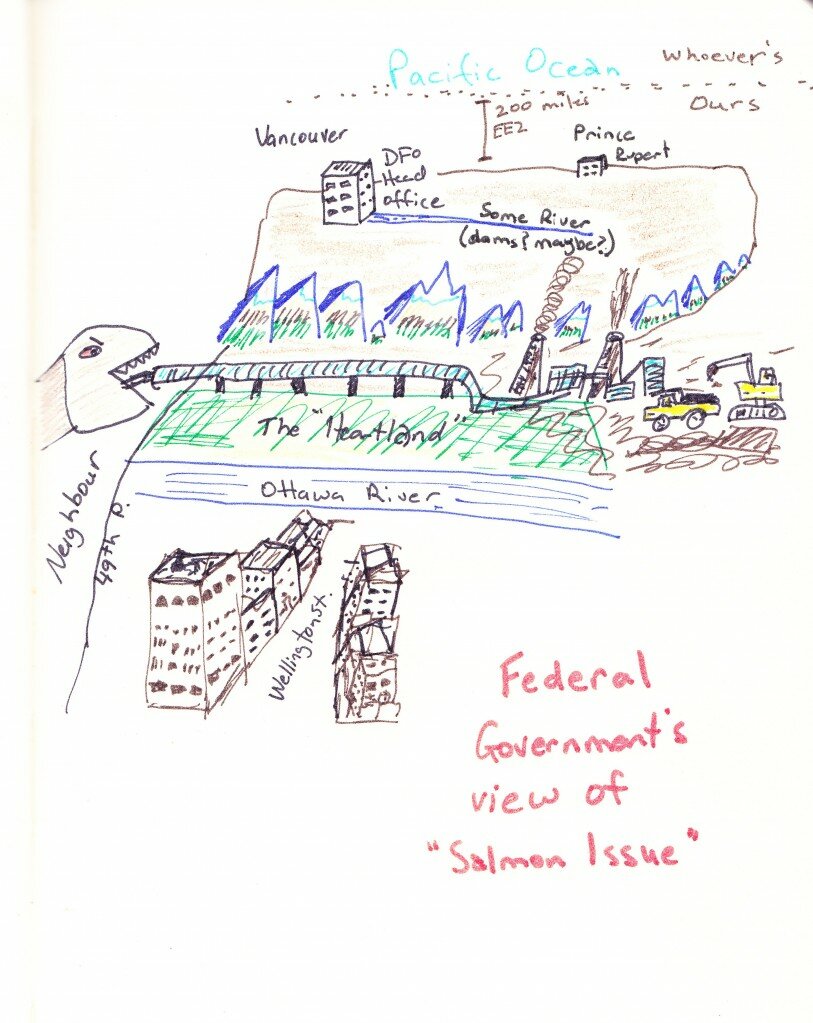

So was there a time when the people of BC and Canada suggested to the federal government that certain departments better find a ‘cheaper’ way to enumerate salmon?

Was there a time when folks said: “hey Department of Fisheries and Oceans, could you please just focus on the large and important stocks only please”?

Could one safely assume then, that if we are only doing enumeration programs on “large and important stocks” that we’ve largely given up on the small and vital stocks? That habitat for all stocks is not really all that important? That when ‘economic’ commercial fisheries have largely disappeared that there will be little purpose in counting salmon?

What would the 100,000 or so strong Gumboot Army in BC — folks dedicated to local streams, streamkeeper groups, volunteer NGOs, etc. — have to say about this?

The trend of counting salmon in BC — is brutal — cuts, after cuts, after cuts have meant enumeration programs up and down the coast of BC, all through the interior, and so on have disappeared.

Often meaning we have little year-over-year comparisons to see just how bad the salmon collapses really are — especially in the millions upon millions of small streams in B.C. The small streams that collectively may represent more salmon than any of the big systems, e.g. “large and important”.