some good comments here – however one significant correction. Media over the years (and other folks) have done a brilliant job of pandering the idea that First Nation salmon fishing (”traditional food fishery”) is having a devastating impact on salmon stocks.

It’s not a tough perspective to market – those of us that spend time on BC rivers see First Nation people with various nets, dip nets, and whatever else. Memories of media stories and misinformation abound – and assumptions are easily formed.

The actual numbers are tough to ignore though (an important component always missing from any media reports).

Commercial and sport catch of salmon in BC: approximately 95% of total.

First Nation catch of salmon in BC: approximately 5% (and this is on the high side).

These numbers do not account for the significant catch of BC-bound salmon in high-sea fisheries outside of Canada’s 200-mile zone throughout the North Pacific. (who is counting this catch?)

This also does not even start down the complex road of the legal environment in Canada in which First Nation catch is allocated – i.e. aboriginal rights and title.

To put things in perspective. Some scientists (Northcote and Atagi 1997) estimate that in the 19th century 120-160 million salmon returned to the Fraser river in a good year (the paper is from a book called Pacific Salmon and their ecosystems: Status and future options – you can find a good chunk of the book in Google books, as it’s about $250 otherwise).We are now seeing salmon runs that are 90% less than that and these sorts of numbers are seen throughout the range of Pacific Salmon. That’s about 100 years to decimate salmon populations.

Might need a bit more than a judicial inquiry on just the Fraser.

The last twenty years has shown that judicial reviews and numerous scathing reports from the Auditor General has not changed much in the bureaucratic behemoth known as Fisheries and Oceans.

It probably can’t be stated enough that this is the same institution that ‘managed’ East Coast Cod into oblivion – including the countless communities that relied on that fishery.

Monthly Archives: December 2009

heretics…positively negative, or, negatively positive?

In reading a bit of old and a bit of new I had one of those synchronous moments that one shouldn’t really ignore. It’s not a blinding, flashing lights and thundering noise type of synchronicity – just a small ‘hey-that’s-kind-of-curious’ type synchronicity.

It came around the term ‘heretics’. An online dictionary suggests that a heretic is: “a dissenter from established religious dogma.”

Yeah, I get that. It’s a term that most of us are somewhat familiar with – burning at the stake, heads cut-off, thrown to arenas of hungry lions and the like.

Now in in this particular case I came across Edward de Bono discussing heretics; as well as – both writers and thinkers that I have mentioned in previous postings. de Bono’s reference came in his 1987 book Letters to Thinkers: Further thoughts on Lateral Thinking. Godin’s reference came from one his most recent books .

Godin’s book, like most of his books, is a quick easy read with no shortage of good, fun ideas. As he suggests, the book’s premise is: “that leadership is the best marketing tactic to any organization–a company, a school, a church, a job seeker…. Our role today is to find, connect and lead tribes in order to make change happen.”

Early in his book Godin brings up ‘heretics’:

…By challenging the status-quo, a cadre of heretics is discovering that one person, just one, can make a huge difference.

Heretics are the new leaders. The ones who challenge the status quo, who get out in front of the their tribes, who create movements.

The marketplace now rewards (and embraces) the heretics. It’s clearly more fun to make the rules than to follow them, and for the first time, it’s also profitable, powerful, and productive to do just that.

This shift might be bigger than you think. Suddenly, heretics, troublemakers, and change agents aren’t merely thorns in our side — they are the keys to our success.”

Now keep this in mind, as I attempt to work in de Bono’s pondering on heretics. (And please bear with me as we slog through this essay-like posting…)

If we believe in a sort of Darwinian evolution of ideas, then being negative has a strong place. Negativity would provide the hostile environment in which only the fittest of ideas would survive. It would follow that these ideas were best fitted to the environment just as surviving animals are best fitted to their environment. Here we come to an interesting point. To what environment are the surviving ideas best fitted? If it is the hostile environment of negativity then only the most bland of ideas is likely to survive… If negativity is directed against change then the surviving ideas will best fit the existing framework. By definition such ideas will be unlikely to change frameworks.

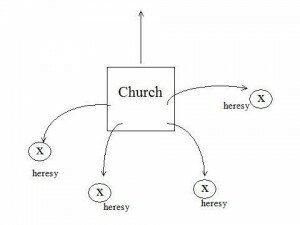

This is an approximate reproduction of de Bono’s hand drawn image in the book illustrating his thoughts that the “fittest” ideas that pass through the ‘negativity’ mine field are generally the most bland and likely to change nothing.

This is an approximate reproduction of de Bono’s hand drawn image in the book illustrating his thoughts that the “fittest” ideas that pass through the ‘negativity’ mine field are generally the most bland and likely to change nothing.

So the purpose of negativity could be to provide the hostile environment that might ensure the Darwinian evolution of the best ideas. There is another purpose for negativity. This is the positive purpose of seeking to improve the idea by removing its weaknesses, or at least focusing upon them so that the designer of the idea can improve these aspects. It is not often that negativity has this constructive intention. It does not, however, matter what the intention might be, provided the person receiving the negativity chooses to treat it as constructive. I have always felt that negativity of this sort is a vote of confidence in the thinker…

de Bono goes on to ponder the philosophy of Hegel that suggests in the clash of thesis and antithesis comes a great idea – or synthesis. As de Bono rightfully points out, one cannot be so sure that the ‘synthesis’ is necessarily a combining of the best of the both, or an entirely new idea that follows the clash of the two. And really, the clash of the two often just results in deeper polarization and simply entrenches the opposing ideas instead.

Moving along…:

It has long been the aim of education to promote critical intelligence. Debate and argument are much encouraged. Scoring points and claiming victory is the aim of the debate. It is claimed that the triumphant view is the correct view. This is because it is logically more consistent with both feelings and knowledge. It is also hoped that that the triumphing view will lay before the audience those insights that allow them to apply their ready-to-be-applied emotions. So the suspicion must remain that debating is a skill (rather than an intellectual exercise) if the outcome is to be determined by the listeners. The attraction we feel for the debating mode is partly historical. In the Middle Ages the thinkers of the world were thinkers of the Church. All educated men were educated by the Church, and the best of them became thinkers for the Church. The purpose of Church thinking was – quite correctly – to preserve the doctrine and theology of the Church in the face of innovators who were usually called heretics.

To prove a heretic wrong was to prove the Church right… It says much for the cleverness of the heretics that they forced through some radical changes in the Church thinking. [there was also a bunch of folks burnt at the stake or met other nasty demises]. It could also be said that in such cases the heretics forced an insight by focusing on areas not yet subject to focused thinking. As in so many other instances, we see here negativity in defence of the status quo. ‘If you wish me to change, prove to me that what I am doing needs changing.’

This is an adaptation of de Bono’s second illustration:

In practice these intellectual justifications for negativity tend to be less important than the emotional justifications. To prove someone wrong means that you are superior to that other person [or a periodic asshole]. To agree with another person makes your individuality superfluous [or protects your ass – i.e. think married life]. It also makes you a follower. Being negative gives an intellectual sense of achievement that cannot be equaled by more constructive attitudes. If you succeed in proving someone wrong there is an immediate and complete achievement. Contrast this with the putting forward of a constructive idea. With a constructive idea there are two possibilities. The first is that you must show that the offered idea does work. Instant proof is usually only possible in mathematics, occasionally, with insight. In other cases it may take weeks or years before the suggested idea can be shown to work. If the value of the idea cannot be demonstrated instantly then a person offering the idea has to hope that the listener will like it. It is rather like telling a joke: if the listener does not think it funny then no joke has been told. That is a weak position to find oneself in.

Outside the world of business, defence is the most consistent survival strategy. In religion, science, politics and art, it may be enough to defend an existing point of view against all attack. In the world of business the reality of the market place makes defence an inadequate intellectual strategy.

There are virtues in negativity, but most of them can be achieved in other ways..

So how many heretics does it take to change a light bulb at the offices where wild salmon are apparently ‘managed’?

What if the individuals responsible for looking after salmon runs were in an organization run like a business? You know the type of business where remuneration is dependent on performance.

Truly, as de Bono points out, in science and politics it’s simply enough to defend an existing point of view – maybe throw in a government union that makes it a little tougher to fire due to incompetence or terrible performance – and presto we’re looking at a real live cod (I mean salmon) (I mean cod) population collapse.

Why? well it’s easier for scientists (and politicians) to debate the complexities of climate change, decadal oscillations in the North Pacific, shifting feed patterns, which way the Aleutian Low is circulating, and whatever the complex-factor-of-the-day is – as opposed to simply admitting that the ‘science’ behind fish management is guesswork at best (come on, we’re not out there actually counting every spawning salmon, so how can we really know how many are there and how many we can catch?).

If we’re guessing – then let’s maybe be a bit more cautious. And rather than hiding behind a curtain of ‘science’; go and truly sit down with the individuals that know individual runs of salmon in specific streams and areas.

One would think that after this many years of screwing it up – that maybe someone would seek assistance… not to mention a few solid wrist slappings from judicial inquiries and Auditor Generals.

If I was in a business that forecast $10 million in profits (i.e. 10 million sockeye salmon forecast to return to the Fraser – 1 million actually showed up) and I only produced $1 million in profits — I think I’d be in deep shit. I think my shareholders would have my head.

Unfortunately, when it comes to wild salmon there is no TARP program, as there is for US banks that are apparently “too big to fail”.

Are there some heretics that will change the game – troublemakers, change agents, thorns in side, as Godin suggests – the keys to success?

thinkers (and stories)

One of my favorite ‘thinkers’ and authors is . He’s written a good stack of books – 62 says his website – on creative thinking. He also teaches courses around the world on direct thinking. Some of his better known books (and processes) are “lateral thinking”, which is now part of our everyday language, and the Six Thinking Hats.

One of his books that I’ve had for over a decade now is Letters to Thinkers: Further thoughts on Lateral Thinking. I was given the book by a fellow I met in Belize in 1999. He was on his way back north to Canada after traveling through South America for close to a year. An appreciator of ‘thinking’; he said the book had been great for provoking various pondering while sitting on a train, or waiting for some bus.

I think the book was one of my initial introductions to de Bono and over the years I have borrowed many of his books from various libraries.

In Letters to Thinkers de Bono talks about ‘stories and metaphor’:

Stories and metaphor are most useful for carrying lessons and principles. There is much more appeal than with a simple statement of an abstract point. A story is much easier to remember. Metaphors are not meant to be extended or worked over in detail. Once the point has been made it floats free and must be challenged as such. The metaphor is only the ‘carrying case’. Destroying the metaphor does not destroy the principle. Occasionally, there is a delight when exactly the same story can be used to illustrate the opposite principle…

A good story – no matter how amusing – never proves a point in an argument. Nevertheless a story can show a type of relationship or process which becomes a possibility. Once it has been thought a ‘thought’ cannot be unthought.

Ordinary language is rather poor at describing complex processes and relationships. It is much better at describing things. We are beginning to inject into language ‘function’ words which do manage to convey functions. Such words as ‘threshold effect’, ‘take-off point’ and ‘win-win situations’ are a step in this direction. Some people are inclined to dismiss such words as jargon – which they may sometimes be – but there is a usefulness in higher order language which allows us to deal with processes as well as things. As suggested above, once the possibility of a certain type of interaction is raised then that possibility must be considered.

To say that ‘this is a threshold type of investment’ means that nothing might happen for quite a while; there is nothing to be seen; then – when the threshold has been exceeded – it all begins to happen. In other types of situation the same thought might be expressed with the term ‘critical mass’ (this suggests that nothing happens until there are enough interactions for an explosive effect to take place).

So there is a spectrum from words to ‘function’ words to metaphor and on to stories. What I like about stories is that the listener [or reader] can see not only the obvious meaning but also other levels of meaning.

(It should be pointed out that de Bono first published this book in 1987 – about 20 years before Malcolm Gladwell published .)

To illustrate his point de Bono hand drew the following image:

He also tells this great little story about a friend of his who owns an avocado farm in California and also has two dogs. One of the dogs took a liking to eating avocado pears – especially when he wasn’t supposed to. The other dog had no interest. To teach the avocado-eating dog a lesson, the farm owner sprinkled – rather liberally – avocados with cayenne pepper. The avocado-eater noticed quickly and left a bunch of half eaten avocado pears. The other dog took an interest, and took a bite. He loved it and ate all the cayenne sprinkled avocados.

Now the farmer has two avocado eating dogs.

What are morals? asks de Bono:

1. That obvious strategies may turn out to be counter-productive.

2. That dogs, like people, are unpredictable.

3. That if you make something spicy enough at first bite you might entrain a buyer.

de Bono, for me, highlights my hope and purpose here – to tell stories that: “can show a type of relationship or process which becomes a possibility. Once it has been thought a ‘thought’ cannot be unthought.”

Exactly my point, as the time for salmon ‘management’ through the 1900s has now past. Now that we are about to see the coming to an end of the first decade of 2000 – maybe it’s time for some new stories, new metaphors, new function words, and even new words – especially in relation to wild salmon?

No one ever asked…

On the first leg of my bicycle trip – The Wild Salmon Cycle – I rode the Dempster Highway from Inuvik, Northwest Territories to Dawson City, Yukon. I’m not sure if it was the smartest idea to select one of the most challenging roads to ride on my planned route of the time – however, I had to start somewhere.

I remember initially finding out that there were Pacific salmon in the Mackenzie River – it was sometime in the late 1990s. When I decided to do the Wild Salmon Cycle I got several surprised comments from people such as: “why the hell are you starting in Inuvik… isn’t that in the Arctic?”

Or something along the lines of: “there’s salmon in the Arctic?”

I did a bit of research and didn’t really find much other than stats that tracked the few salmon that migrated up the Mackenzie River – specifically some chum in the Peel River, a large western tributary of the Mackenzie that runs through the eastern Yukon.

The map that really set my mind running and eventually culminated in the Wild Salmon Cycle was this map showing the range of Pacific salmon in North America produced in the late 1990s by the enviro-based organization in their book ““:

One of the stories circulating as I set out on the ride was that due to climate change/warming trends, some Pacific salmon were colonizing streams east of the Mackenzie and were moving east across the Arctic. When I heard this story I had a couple of questions:

1. Had anyone really looked before? There’s a difference between “we were always looking and never saw any salmon'”and “we had a long time assumption that no salmon were there and then when we actually went and looked we found some salmon – gee this is amazing they must be moving east…”

2. Had anyone asked the people that have been there for eons?

It was late July when I arrived in Inuvik and on my first night in town, the sun set to just a small sliver along the horizon at midnight before coming back up again. I distinctly remember finally falling asleep in my tent that first night in Inuvik around 2 a.m. and hearing kids out playing – why not, the sun was up? As I set out riding down the Dempster – read the stories in forthcoming book (i.e. what the hell was he thinking?) – I reached the Peel River crossing. It was quite late in the day – almost midnight – but still full daylight.

I managed to make the last ferry across the river for the night. On the ferry, I met one of the crewmen a local First Nation fellow from the nearby community of Fort MacPherson. He asked lots of questions and laughed a lot with his toothless grin. He told me to go stay in his fishing cabin. He pointed it out from the ferry and told me the door was open. Beat setting up the tent in the oppressive black-out of mosquitoes.

The mosquitoes were so bad that I was riding in 30 degree Celsius (about 90 F) weather with my rain gear on and duct tape on the sleeves. Uphills were torture, not just because it was gravel, and I was overloaded with gear, and I was not in great shape (yet) – but more because the mosquitoes would descend on me in layers. I would grit my teeth – literally – so that I didn’t have insect lunch on every breath. I was nervous that with all the hard breathing through my nose I’d suck mosquitoes into my sinuses – thank ghad for nose hairs…

It was horrendous – until the wind blew… then I could actually enjoy the views.

After spending the night in the cabin, and realizing that it was tougher to kill all the buzzing divebombers before falling asleep – then in a tent. I woke up and walked down to the river. I saw a lady in a canoe checking her fishing nets. I asked her if she minded if I took some pictures.

“Not at all” she told me in her thick northern accent. She was an elder from the nearby community, in her 70s. And here she was on her own hauling in the net from her canoe with some pretty darn big fish. I asked her about salmon, and whether she caught them in her nets.

“oh yeah, all the time” she explained.

“For how long?” I asked.

“Always” she said, “my grandmother used to catch them too.”

I told her about this theory that more salmon were showing up in the Arctic, and moving east across the Arctic.

“oh, they’ve always been here…. it’s just that no one ever asked.”

Searching for One Percenters?

As I set out to finally compile and write a book or two on the topic of salmon and on the Wild Salmon Cycle (the 10,000 km bicycle trip I completed in 2003 through the North American range of Pacific Salmon) – and before launching this blog – I took a pretty good look around online to see what was being said about “salmon”.

I was pretty damn surprised to find… not much.

Sure, there are the usual advocacy and research-oriented websites – and interesting organizations like . Check them out they do some neat stuff around the entire Pacific Rim and world of Pacific salmon.

Search salmon recipes and you will find no shortage of results, or salmon fishing… look out.

Over the three years that I peddled away completing the Wild Salmon Cycle – and in the years of contract work before that; I had heard about, heard from, and met a rather impressive array of people involved in salmon-related conservation, stewardship, and/ stream cleaning projects. I met people active for years on salmon-related projects in the Sacramento River in California, the Eel River towards northern California, I saw signs for projects near Olympia, Washington, I worked on salmon stewardship projects in the Yukon on the Yukon River, I met people involved in projects in Alaska, and as I mentioned in a posting yesterday there is a veritable Gumboot Army charging around the streams of BC – some suggest over 200,000 strong.

So then why can’t I find so much more in this age of social media and social marketing?

I’m not sure why and I am set on finding out.

In earlier postings I have mentioned Seth Godin a few times – social marketing guru. I’ve also mentioned he’s a pretty neat guy, and also has one of the most popular going. This month he released another free called “What Matters Now“. It’s a collection of thoughts from a wide range of folks. It’s a good read, with links to all the writer’s blogs, books, and websites featured in the book (haven’t waded through all that yet).

One of the pages in the books is called “1%”.

The story is about a couple of folks who created a product called “Bacon Salt”. Sounds rather obscure and odd, however it’s bacon-flavored salt. The two folks who created it had no food experience and no marketing budget. So what do they do?

They go online and through social marketing they find bacon enthusiasts; strike up a conversation, and eventually through a small percentage of the people contacted word starts to spread. A few months later the buzz is increasing. All of a sudden articles, TV appearances and the coup de grace: Oprah. They launch a bunch of other bacon flavored products and a successful brand is created.

The key to the success is that it didn’t begin with a social network of millions of members, and even if it did those millions wouldn’t be the buzz-spreaders – it was a tiny percentage of the enthusiasts that started the buzz.

Approximately 1% – these are the One Percenters.

The authors of this little piece suggest that the One Percenters:

“are often hidden in the crevices of niches, yet they are the roots of word of mouth…. This year your job is to find them and attract them.“

So in this Pacific Rim niche – I am searching for the one percenters of salmon enthusiasts…. I would like to feature stories, tell stories, read stories, and maybe even generate some buzz along the way.

"red/yellow/green" system… maybe-proof your organization

So it’s 11 p.m. at night and I am up rocking our new baby to sleep, as he’s a bit confused about the difference between day and night.

As I was rocking, I’ve been reading Seth Godin’s book: small is the new big: and 183 other riffs, rants, and remarkable business ideas. It’s a collection of Godin’s blog entries that he decided to publish once he reached one thousand entries.

I came across one that got me thinking about the Wild Salmon Policy – yeah apologies, another suggestion or two for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) and/or the politicians that bring about political will for change.

See, back in the late 1990s I caught wind of this innovative new policy that DFO would be introducing. It would change the way wild salmon were managed on the West Coast. This was not long after the years of “zero mortality” on coho. In the mid to late 1990s, coast-wide in BC, coho declines had a lot of people more agitated than members of parliament exposing another ‘scandal’ – so a zero mortality policy was adopted and all coho caught were to be released.

(side note: I’d be curious to see stats from that year on seals, sea lions, and orcas that simply hung around sport fishing boats and fishing lodges and gorged themselves on the ‘catch-and-release’ coho that were released and either floated belly up or began sinking to the bottom. Next best thing than just having salmon injected intravenously.)

(not to mention the number of coho that accidentally landed in the back of pick up trucks near sunset…)

In 2000 and 2001 I began to hear a lot more about the Wild Salmon Policy. At that time I took on a contract with one of the larger environmental organizations in BC. My job was “Gumboot Campaigner” and I was to meet with community organizations around the Vancouver Island and the Lower Mainland and organize an active voice, which would then be coordinated to affect how and when the Wild Salmon Policy would be implemented.

Estimates at that time suggested that somewhere in the neighborhood of 200,000 people around BC were active in salmon-related projects – from streamkeeper organizations to weekend creek clean-up efforts. Regardless of the number; it’s significant. The Gumboot Army – as they were, or have been, labelled. (I’ll write more about this in future postings).

So it’s now the sunset of the first decade of the 2000s. In a little over a week we will be into 2010. The Wild Salmon Policy is still not fully, or effectively implemented in BC. Over a decade of consultation, changing (aka bickering) governments, watering-down, beefing-up, strategizing, visioning, brainstorming, break-out groups, PowerPoint, spreadsheets, lost agendas, and enter other bureaucratic bumblings [here].

Godin has a great little riff that could shift things… “maybe-proofing your organization”. The strategy is the “red/yellow/green system”. Godin explains it like this:

Is it possible to manufacture little emergencies so that everyone in an organization has to say yes or no? Is it possible to create … decision situations when, simply sitting there inertly isn’t an option? It is possible to create a “maybe-proof” organization.

Some of the best project management that I’ve ever seen has happened in companies that use the “red/yellow/green” system. It’s based on a very simple, very visible premise: Every single person in the division of a company that’s launching a major new initiative [or policy] has to wear a button to work every day. Wearing a green button announces that you’re on the critical path. It tells everyone that the stuff that you’re doing is essential to the product’s launch – that you’re a priority. If you don a yellow button, you’re telling your coworkers that you’re on the periphery of the project, but that you have an important job nonetheless. And wearing a red button sends the signal that you have an important job that’s not related to the project.

When someone with a green button shows up, all bets are off. Green buttons are like the flashing lights on an ambulance, or the requests of a surgeon in an operating room: “This is a life-or-death path,” green buttons say, “and you’d better have a damn good reason if you’re going to slow me down.” When a person wearing a yellow or red button meets up with someone wearing a green button, that person understands that it’s time to make a decision: “How can I help this green button get on with the critical job?” Or, at the very minimum, “How can I get out of the way?”

Of course, people can change their button color every day, or even several times during the course of a meeting. But once you adopt the button approach to project management, several things immediately become clear: First, any company that hesitates to make people wear buttons because it’s worried about hurting employees’ feelings isn’t really serious about the project – or about creating a culture in which decisions get made. In fact, if you duck the buttons, you’ll just keep ducking other decisions. Second, folks don’t like wearing red buttons: They’ll work very hard to find a way to contribute so that they can wear a green button. And there are plenty of people who are totally delighted to wear a yellow button. Third, the CEOs, project leaders, and team leaders can quickly learn a lot about who’s accomplishing what inside of a company.

Godin asks: “Would it make you take an important – if painful – look at your own decision-making style if you were issued a button each day that signaled your decision-making readiness?”

Good ideas; bad ideas

Lately, I’ve taken a liking to ‘s books and . The fellow writes in a matter-of-fact way, has a fun way of presenting ideas (for example, he wrote a book called Purple Cow and I think the first 10,000 released came in a kind of milk carton), and he has no qualms about sharing other people’s successes and links to websites, blogs, etc.

One of his other books is called The Big Moo: Stop trying to be perfect and start being remarkable.

The guy doesn’t mind just throwing it out there – and he’s been very successful doing so, plus in the meantime has done a great job of promoting some interesting people, projects, and ideas. He also doesn’t have many qualms about pointing out brain farts and other hiccups.

Today on Godin’s blog he has a posting about ‘ideas’. Many of his postings are short and to the point (maybe something I can learn from…) so I hope he doesn’t mind me sharing his posting it’s called:

“”

A few people are afraid of good ideas, ideas that make a difference or contribute in some way. Good ideas bring change, that’s frightening.

But many people are petrified of bad ideas. Ideas that make us look stupid or waste time or money or create some sort of backlash.

The problem is that you can’t have good ideas unless you’re willing to generate a lot of bad ones.

Painters, musicians, entrepreneurs, writers, chiropractors, accountants–we all fail far more than we succeed. We fail at closing a sale or playing a note. We fail at an idea for a series of paintings or the theme for a trade show booth.

But we succeed far more often than people who have no ideas at all.

Someone asked me where I get all my good ideas, explaining that it takes him a month or two to come up with one and I seem to have more than that. I asked him how many bad ideas he has every month. He paused and said, “none.”

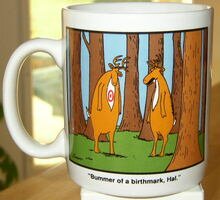

OK, so yes, I recognize that I did say in an earlier posting that the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) is an easy target. When you’re such a big bureaucratic behemoth (B3) the bullseye is inherent. Kind of like the old Far Side cartoon:

(thank you Gary Larson)

So maybe now the bureaucratic behemoth is due for a long series of good ideas. For example, the old Habitat Restoration and Salmon Enhancement Program (HRSEP) from 1997-2002 wasn’t such a bad idea – about $35 million over a period of 4-5 years put into habitat related projects. And not such a bad idea to try and put that money into community groups that actually know what’s going on in their local streams.

Money into on-the-ground projects implemented by local citizens and community groups – good idea.

Only funding the project for about one salmon life cycle – bad idea….. many community groups went from $0/year to $300,000/year back t0 $0/year in less than five years.

Spending $15-17 million on research every year (see post from yesterday) and next to $0 on local community groups implementing effective habitat and monitoring programs – not so good idea.

I don’t think I could fully list the bad ideas – however, in the spirit of Godin’s post: ‘you can’t have good ideas unless you’re willing to generate a lot of bad ones.’

What if we were due for a bunch of good ideas…?

Don't implement solutions. Prevent problems. (look upstream)

On my visit to the local library today I came across a book: Rules of Thumb: 52 Truths for winning at business without losing your self. The book was written by ;one of the cofounders of Fast Company Magazine.

The book was displayed on the new arrivals area and I figured maybe it was worth a flip through.

Webber’s Rule #4 is the subject line of this post: “Don’t implement solutions. Prevent problems.” In this rule Webber suggests:

“Putting solutions into effect seems to be where the action is… But what if the real action isn’t with solutions? Focusing on solutions misses an essential point: preventing problems in the first place. There’s an even more important idea then execution. It’s the idea of early detection, intervention, and prevention. Business leaders who embrace that idea can point at something even better than implementation. They can point at massive savings and better outcomes”

[kind of like early screening for breast, prostate, and other cancers…]

Webber discusses a colleague’s success in an early intervention program with high-risk youth in Pittsburgh where students participate in “education, training, and hope programs” – the . As Webber points out, this program may be the “only antipoverty, anticrime educational program in the world that has also won four Grammy awards” – they record and compile performances of top notch artists at the facility – then sell the albums to help finance the program.

Sounds like a great program and something I can definitely relate to after several years of coaching various youth sports and being a youth worker for a few years.

“So What?” asks Webber. Well… as he aks:

“Why haven’t we been able to apply it [prevention, early detection] in a host of public policy areas? We know that prevention and early intervention work in everything from health care to energy policy to public education to transportation. But these well-entrenched systems seem intractable, despite economic and social evidence that proves how much more effective and less expensive a different approach would be.”

“At the top of major corporations [and government departments] leaders habitually look the other way when they know a serious problem needs their attention, hoping the day of reckoning won’t come on their watch. Or they pound the table and demand a fix – without ever acknowledging that their inattention to the root cause of the problem only drives up the cost of any solution, which is often not a solution but a palliative.

You could chalk it up to human nature: denial, hope against hope that somehow the inevitable won’t happen, at least not yet.

But there is another component to human nature, and all it takes is practice: look reality in the eye, establish an honest assessment of the real nature of the problem, look upstream to see its true causes, and then roll up your sleeves and attack it early, deeply, and effectively.”

It would be hard to agree more with Webber’s conclusion to this thought: “In the end it’s not only cheaper and more effective. It also represents leadership and very valuable skill.”

What if government bureaucracies tasked with looking after salmon could take this approach?

This is the best you've got!?

Surfing through various headlines, articles, riffs, and rants – some of which I am posting here – I came across this September 09 news release from the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Now, I know this department is an easy target – however, this press release floored me.

On their website, DFO has all of their from the past several months. In the past several months, the only press release I came across regarding West Coast salmon is:

“”

The press release states:

“The lower than expected returns in certain West Coast salmon runs have generated significant interest and concern in the Department and among all Canadians. Questions have been raised about DFO’s commitment to funding research and sustainable fisheries, particularly the Fraser River sockeye.

The Department’s first priority is the conservation and long-term sustainability of sockeye in managing the fishery. Accordingly, the Department has annually invested significant funds to carry out vital scientific research and monitoring.”

2002-2009 Annual Expenditures for West Coast Salmon Research

- 2002-2003 $17.9M

- 2003-2004 $16.8M

- 2004-2005 $16.3M

- 2005-2006 $16.1M

- 2006-2007 $16.5M

- 2007-2008 $15.9M

- 2008-2009 $17.0M

Are you frigging kidding me!?

The West Coast of Canada experiences one of the worst years on record for actual fisheries and sees some of the largest population crashes on record (e.g. Fraser sockeye: over 10 million forecast; just over 1 million return) – and the best the federal department, responsible for ensuring salmon populations are healthy, can send out is a press release stating ‘look at the money we’re spending on research’.

Again, are you frigging kidding me?

This is like me telling my kids in twenty years; what do you mean I don’t care about you look at all the money I spent on you over the last five years: $10,000 for hockey; $5,000 for dance lessons; $20,000 in dad’s taxi services…

NO, no and no – commitment is not assessed by spending $$.

This is like the Mastercard commercials:

- phone calls from Prime Minister’s office to boycott December SFU salmon think-tank: $105

- rookie DFO Minister recent BC travel costs to skip meeting with anyone: $100,000

- new DFO research vessel to park in Victoria harbour: $2.5 million

- DFO policy of empty press releases, stating and doing nothing: PRICELESS…

Maybe a few comparisons to some other areas of federal research funds may shed some further light? For example, how much is the federal government spending on tar sands research; or the Mackenzie Valley pipeline, or….?

As I recently heard an NHL hockey coach suggest between hockey periods: “we need to pull our heads out of our proverbial butts….”

Salmon in London?

Came across this news article on Bloomberg about Atlantic salmon in the River Thames in London.

“Oct. 14 (Bloomberg) — Twenty thousand juvenile salmon were released in a River Thames tributary outside London last year to see if they would migrate to sea and return home to breed. Only three came back.

Sewage spilling into the river that bisects Europe’s financial capital may be the reason…”

Apparently salmon have not been in the River Thames for almost 180 years – I guess the “32 million cubic meters of waste flow into the river a year” poses some challenges. There are now multi-billion dollar plans in order to try and build tunnels under the river and tributaries to deal with the sewage overflow problem.

The article describes how in 1858 British Parliament was disrupted due to the “Great Stink” emanating from the river…

180 years of no salmon, hmmmm