Unfortunately, this is probably on the top ten list for worst researched, misinformed Fraser sockeye articles.

Globe and Mail, Monday Aug. 30th by Gary Mason (who generally writes sports articles and others…)

From the opening to the close, this article is wrong on so many fronts, although he’s quite right on DFO’s worst blown forecast ever this year on Fraser sockeye.

I left a comment on the article on the G & M page, but one is limited to 2000 characters in those comments. Several others left some not-so-kind remarks — however there was a common theme of ‘more research required prior to publishing’, please.

Mason’s article:

…Worse, even as the sockeye began returning to the Fraser River in droves in late August, DFO refused to allow a fishery. It had to make sure it wasn’t seeing things. Consequently, millions of sockeye were lost while DFO dithered – money that cash-strapped fishermen desperately need.

Wrong, there were several commercial openings for Fraser sockeye as well as an open sport fishery on the river. I’m curious where the salmon were “lost” to?

Oh no, wait… you don’t mean “lost” Mr. Mason… you mean they swam upstream to spawn… Now that’s a novel thing for salmon to do.

I don’t disagree that fishermen are most likely cash-strapped… however, there is no shortage in history of groups of workers dependent on natural resources having to move on to new careers and livelihoods. It’s not pleasant… however, rather common in B.C. and Canada — often as a result of mis-management of the natural resources in question in the first place.

North Atlantic cod is the first that comes to mind.

Or how about the B.C. endangered logger? The forest industry is still a disaster in BC and many folks have had to move on to new livelihoods. Or how about entire communities: Cassiar (once a great asbestos mining town), or Tasu (once a thriving mining town on the west coast of Haida Gwaii) — or Rose Harbor (once a thriving whaling community now within Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site) — or Kitsault an old mining town (molybdenum) north of Prince Rupert .

These are unfortunate occurrences — however, do happen. All too often with commercial fisheries, and have occurred in commercial salmon fishing fleets across B.C. Maybe the finger can be pointed to mis-management; however, we have all played a part.

_ _ _ _

Mason’s article:

Alaska harvested more than 170 million salmon in 2009, compared to the near-complete disappearance of the species in B.C. in the same year.

No… not all BC salmon species “disappeared” — mainly just Fraser sockeye — one BC salmon species. Other BC salmon are showing long-term declines, but have not “disappeared”. There were still 10 million salmon harvested in BC last year. Plus, didn’t the Marine Stewardship Council just “eco-certify” all BC sockeye salmon fisheries? And close to ‘eco-certifying’ a bunch of the chum and pink fisheries?

That doesn’t sounds like “near-complete disappearance”… the MSC is apparently “world-leading” in “eco-certifying sustainable fisheries”…

What was thought to be evidence of a complete collapse of the West Coast salmon fishery prompted the federal government to set up a commission to investigate. Then, a year later, 30 million turn up at the door of the Fraser. What gives?

Wrong… there was not a complete collapse of the West Coast salmon fishery (see above); nor, did that prompt government to set up a public inquiry (Cohen “commission”).

There was a significantly blown forecast for Fraser sockeye in 2009 (one species comprising the entire West Coast salmon fishery) and this was the third year in a row there was no Fraser sockeye commercial openings. This is clearly laid out in the preamble to the Cohen Commission.

“What gives?”

Well… Fraser sockeye are cyclical. Just because 35 million+ is now the total 2010 forecast run size for Fraser sockeye does not suggest that all is good in the hood. One of the suggested reasons for a big run this year is favorable ocean conditions (La Nina) coupled with reduced harvests in the four year cycle previously (e.g. 2006 and 2002). Those two years also saw decent returns and some very high effective female spawner estimates.

In three years we are still going to see the return from last year’s run which was suggested to be just over 1 million total — which does not equate to 1 million effective spawners.

_ _ _ _

…

That, to me, sounds like the commission will be examining how the DFO conducts business and sets policies and whether those policies are working.

As a point of reference, Mr. Cohen may want to look at how Alaska baits its hooks.

Yes, I agree with this point. Justice Cohen is mandated to look at how DFO conducts business. Of course, this is the fifth time in the last two decades that this has occurred and changes are slower than mice running in molasses (in the fridge).

Of course the great challenge for Justice Cohen is that policies written on paper are about worth as much as the sheets of paper. Where the mice can run free and clear is in how those policies are actually implemented on the ground. For example, the Wild Salmon Policy, which is full of great words and ideas… but in reality, on the ground, in the real world — poorly implemented, underfunded, bumpf-filled, and near-impossible to actually achieve

For example, true “ecosystem-based management” (EBM)… if we used and implemented EBM, then we wouldn’t be talking about “lost” or “wasted” salmon, when they are simply swimming upstream to do whatever it was that the creator/universe intended for them to do: be food for bears, eagles, racoons, etc. or maybe even spawn… not because “cash-strapped fishers” didn’t catch them and sell them to Wal-Mart at bargain basement prices.

Because the oft-admired Alaskan sockeye fishery occurs well before the BC sockeye fishery… BC fisherfolks are pumping sockeye into an already flooded market. This means lower prices; this means un-economic returns; this means little relief of the “cash-strapped”.

Like anything, selling more doesn’t necessarily mean making more… it’s those wonderfully dry terms of economics called “supply and demand”. Throw in some capacity of the marketplace to deal with an influx of fish, and “houston, we have a problem”. Right now in Vancouver and suburbs, fisherfolks may be catching lots of fish but are being forced to sell them dockside off their boats, as there just isn’t the capacity (or demand) at canneries and fish markets (they’re already aflood with sockeye from other places).

So… if we want to talk “wasted” or “lost” fish — what happens when BC fisherfolks on the Fraser are left with a surplus of sockeye that they can’t sell? I might have some proposed recipes.

(by the way Mr. Mason, I don’t think Alaska does much baiting of hooks, most of their fisheries are net-based)

_ _ _ _

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s Salmon Management Model is one of the most successful in the world when it comes to sustaining a sometimes temperamental species of fish…

Not so fast; as I recommend in my comments to the article Mr. Mason may want to do a web search on the Yukon River Chinook fishery disaster declared on last year’s fishery. See earlier posts on this site: and .

Or the fact that Alaska has one of the world’s biggest salmon ocean ranching programs. See earlier post: or search it online. 2.5 billion salmon fry pumped out into the North Pacific every year from Alaska, all of which will never know a river. 95% of Prince William Sound commercial salmon fishery is ocean-ranched salmon.

So, really, how do we measure or define “most successful in the world”?

Enbridge purports to have “world-leading” safety standards — yet, as their pipeline rupture and resultant spill in Michigan is proving… maybe those “world-leading standards” are simply self-defined on paper…

Plus, it’s not that difficult to be “sustainable” when you have a sparsely populated state, fish that migrate in northern sections of the North Pacific, and wonderful intact habitat… (bit of an apples and oranges comparison… both fruits; but rather different)

_ _ _ _

B.C. fishermen probably should have harvested about 80 to 90 per cent of the current 30-million-plus salmon run. Yet, because of the DFO’s reluctance to open the fishery until it could verify the run size, 10 million fish are estimated to have been lost.

That wouldn’t have happened in Alaska. We should find out why.

As I ask in my comment to the article — show me where Alaska has successfully harvested 80-90% of their sockeye runs for many cycle years and been succesful. Their harvest yields are closer to 50% of total run and have been for decades. DFO’s have been in the 80% range since the 1950s; and we can see what that got us.

I think maybe Mr. Mason has bought a little too much into the fishery suggestions of Dr. Carl Walters who has been quoted in numerous articles and has stated in several radio interviews that we should be harvesting closer to 80% of this year’s Fraser sockeye run.

As I also point out in my comments to the article and in other posts on this site. Over 70% of the Fraser sockeye run this year is comprised of one stock — the Adams/Weaver run is predicted to be over 24 million of a total run size of about 35 million.

There are estimated to be over 200 separate stocks of sockeye in the Fraser River. Many of which are teetering on extirpation or extinction and several smaller stocks that no one even knows their status. And thus, if we run out and harvest 80-90% of the total run… (at the time of Mason’s article the total run size was hovering around 30 million; it’s now upwards of 35 million.)

Therefore, we harvest 80-90% of the run (as suggested by Mason in the article and Dr. Walters in other forums) which leaves 3.5 million (90% harvested) to 7 million (80% harvested) total run size. Subtract off the “management adjustments”, a percentage attached to total predicted marine run size to account for in-river mortality due to water levels and temperatures — that number has hovered around 15% for the Summer Group and 35% for the Late Summer Group (which incl. the Adams run).

Oh… well if we took 80-90% in commercial fisheries and then had to subtract 35% to account for in-river mortality. Well… we’d be at a negative run size: -15% if we harvested 80% and -25% if we harvested 90% (negative run sizes might have BC implementing ocean-ranching tout de suite…)

So let’s say we’re not that stupid. Let’s say we take the total run size, then subtract off the management adjustment (MA), then suggest a 80-90% exploitation rate. Or let’s just pretend there is no in-river mortality (i.e. MA).

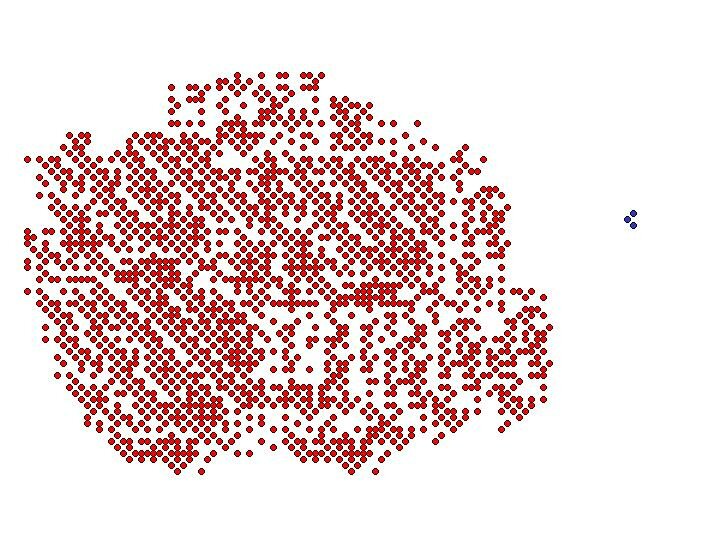

Well… with the estimates of overall Fraser productivity over the last decade (remember this graph):

Salmon Think Tank graph produced by Pacific Salmon Commission Chief Biologist

Let’s give it a healthier than shown productivity rate of 2 adult returns per spawner.

Total run size forecast in marine areas at 35 million: 35 million – 80% exploitation = 7 million fish with potential to reach spawning grounds.

Or,

35 million – 90% exploitation = 4.5 million potentially reaching spawning grounds.

Ok, 4.5 million to 7 million spawners multiplied by an overly optimistic productivity of 2 adults returning per spawner leaves us with a potential total run size in 4 years of 9 to 14 million. That’s about 2.5 to 4 times less than the total run size this year.

If we repeat the same practice in 4 years (2014) we’d have an even smaller run four years after that (2018) — if productivity levels remain low, as many predict them to do so.

This sounds brilliant.

Maybe Mr. Mason should stick to sports and real estate articles.