The other day I had a post: .

In that post, I highlighted some information from a 1950s report: .

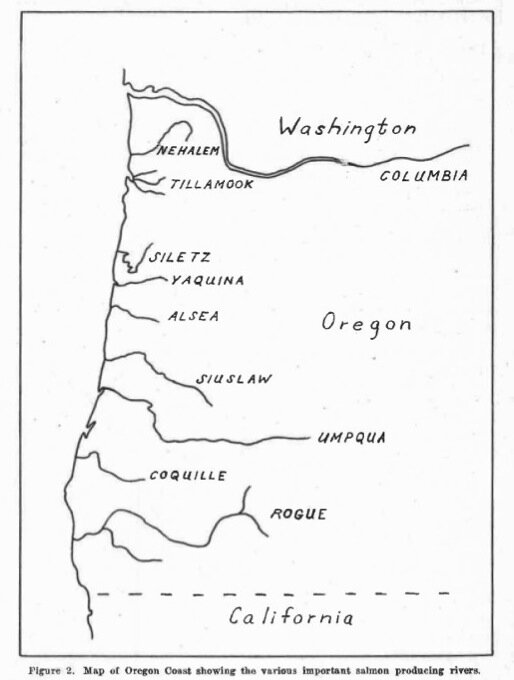

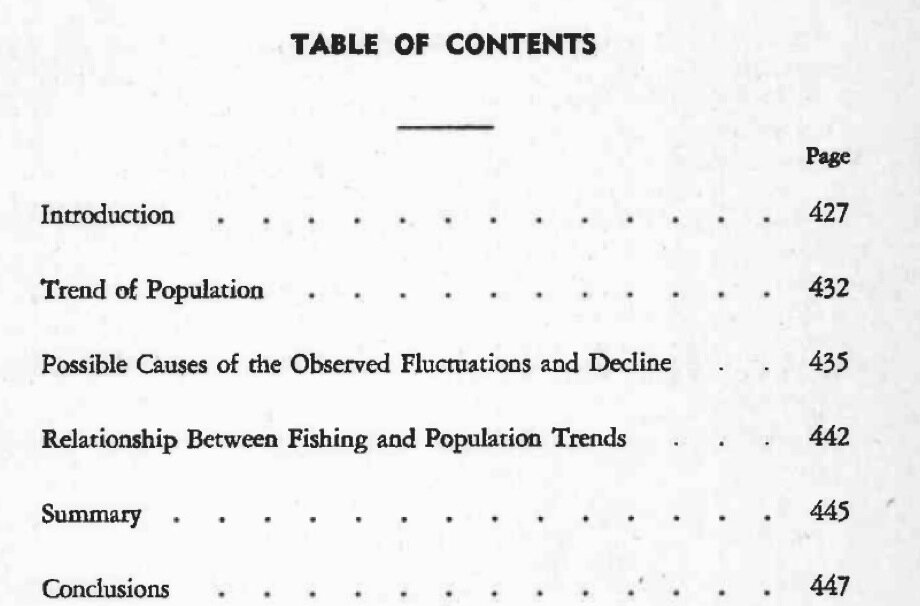

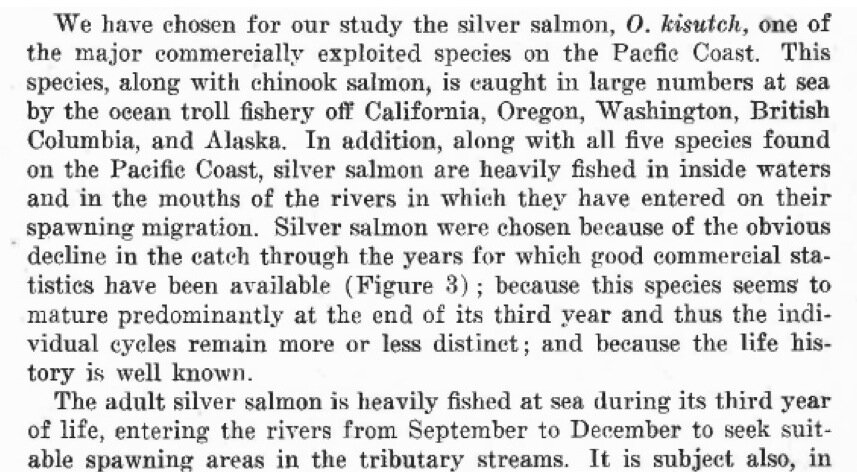

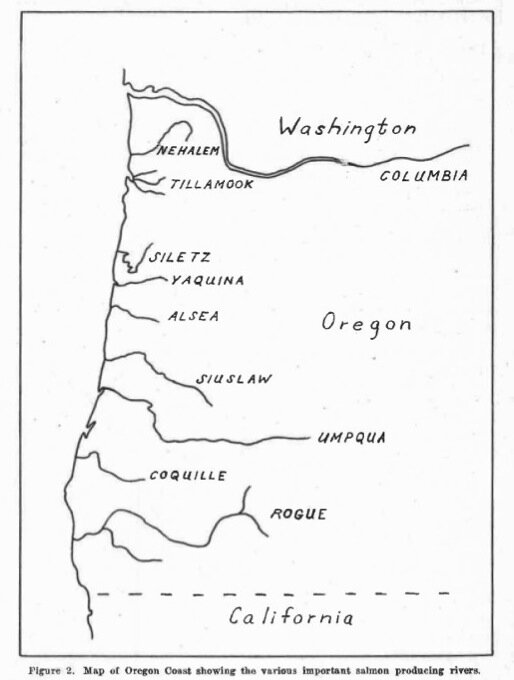

The report focuses on coho runs in certain Oregon streams:

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The trend of salmon populations and specifically of salmon catches within commercial fisheries was rather familiar… dwindling fast.

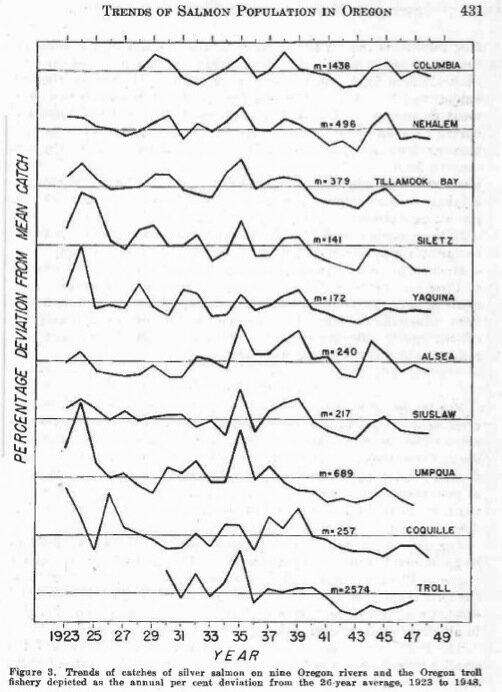

The report looked at commercial fisheries catches in Oregon from the mid-1920s on to the late 1940s.

It was clear in the report that fisheries were having an impact… (seems like a bit of a no-brainer…).

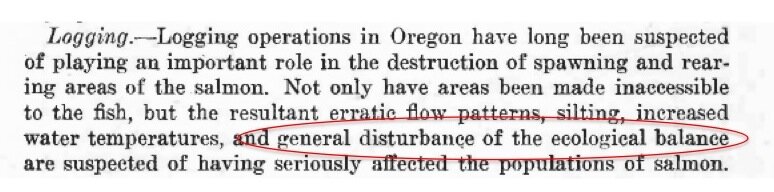

The report also looked at: Other Potential causes such as:

Pollution?, Hatcheries?, Logging?, Waterflow?

Remember this report is from 1950.

Factors dismissed: Pollution and Hatcheries (most were still quite small at this point).

Factors implicated:

_ _ _ _ _ _

The report paints a pretty clear picture of the impacts of overfishing and logging — and in turn the impact of logging on waterflows.

“… resultant erratic flow patterns, silting, increased water temperatures, and general disturbance of the ecological balance…”

Remember this was 1950…

For those in BC who know some of the fisheries history — this was well before the Fish Forest Interaction Program (FFIP) of the 1980s… this was well before studies began in earnest in Carnation Creek on west coast Vancouver Island… that was well before the BC Forest Practices Code arrived in the 1990s. This was before Greenpeace was even ‘Green’ and the “peace” movement was not yet active.

This was when David Suzuki was probably still in grade school… and David Bower hadn’t yet started his rage against dams and facilitating growth of the Sierra Club in the U.S.

John Muir was probably about the only prevalent “conservationist” “tree-hugger”… and he’d been dead awhile…

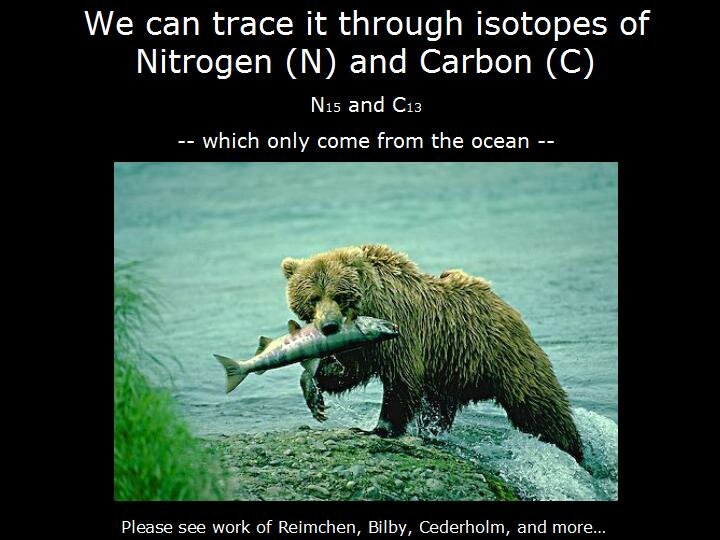

Here is chart comparing the trends in salmon catch to the production of lumber board feet in Coos Bay, Oregon through the 1920s, 30s, and 40s.

I’m sure someone will want to argue that this is coincidence and that correlation is not causation and so on…

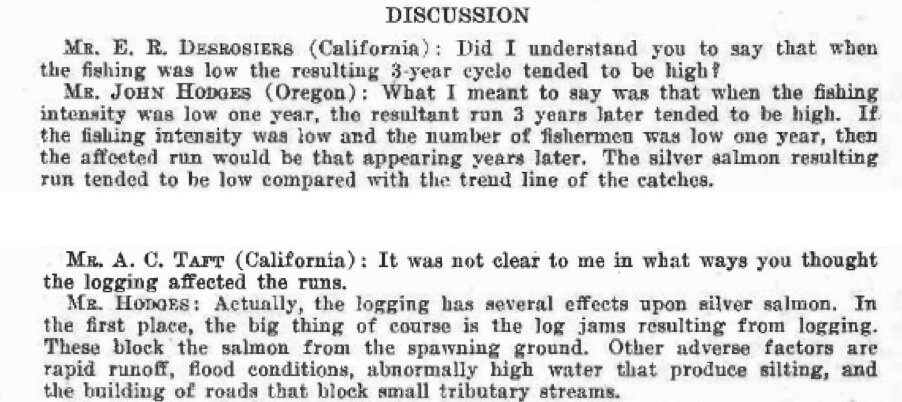

And well… folks did argue against this report. There is transcribed conversation at the end of the report, that really is quite revealing.

I guess Mr. A.C. Taft from California didn’t understand that part about: “… resultant erratic flow patterns, silting, increased water temperatures, and general disturbance of the ecological balance…”

So Mr. Riddell is fronting the age-old argument… “you can’t really tell us here that overfishing could in fact be an impact…? there must be other factors…”

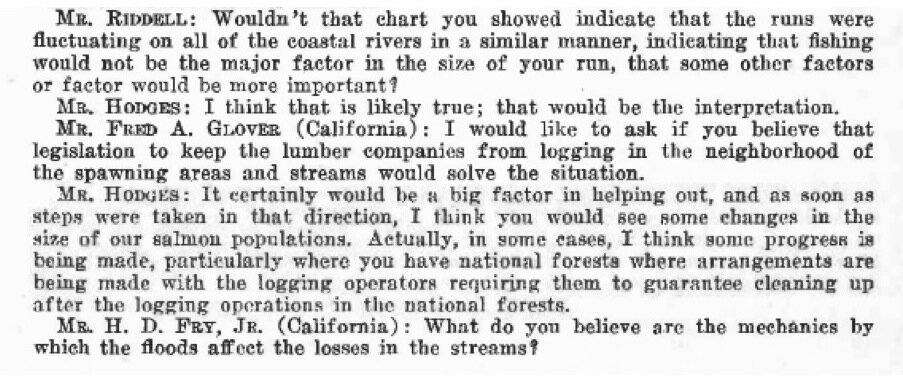

Then Mr. Glover from California… “do you think changing logging practices would make a difference…?”

Ummm, gee, there’s that curious part about: “… resultant erratic flow patterns, silting, increased water temperatures, and general disturbance of the ecological balance…” again…

Hard bit of info to pick up…

Then there’s the question by Mr. H. D. Fry, Jr. “hey… could you explain that point to me again about how intensive clearcut logging and increased water flows are related…?”

Hmmmmm….

Same answer many folks have provided for generations…

Trees are giant sponges. An average tree, especially an old-growth Douglas Fir absorbs and retains an incredible amount of water that falls from the sky. That water is then retained from suffering the full effects of gravity and raging down hillsides through the point of lowest resistance — stream channels. More water running down hillsides means erosion, mudslides, raging debris torrents, etc.

Trees hold hillsides up and stream channels up.

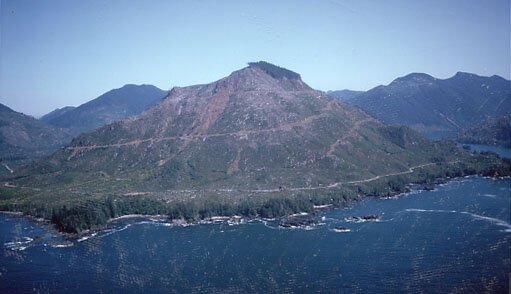

Take the trees off hillsides and very little is holding all that soil on that hillside. Add in 5-9 metres of rainfall, snow, melting snow, and the worse rain-on-snow events, and what happens?

just "natural"

I think the point is clear…

The main point of all this is that for well over 60 years we have known what impacts salmon populations.

In Oregon, folks knew in the 1950s that overfishing and logging were decimating salmon populations and in turn decimating salmon fisheries and in turn decimating coastal communities.

Unfortunately, overfishing and overlogging carried on in the Coos Bay area for quite some time after this rather clearly worded report.

Have you been to Coos Bay, Oregon lately?

It’s a nice area, however last time I was through the downtown was gutted with more “for lease” signs then business signs.

The population peaked around 15,000 people in the 1970s and hasn’t changed much since.

Is the story of Coos Bay and salmon and logging — all that different then say any Eureka, California or Port Angeles, Washington or Port Alberni, BC or Port Hardy, BC or Port Clements, BC… or Port Edward, BC… or… or… or….

And yet it doesn’t seem to matter what local knowledge says in these communities. Folks have been sitting there ringing alarm bells saying: “this is not sustainable, this pace cannot be maintained, our communities won’t survive this…”

“This is boom-and-bust…”

“We are upsetting the ecological balance…”

And the response is: “sit down and shut-up you darn tree hugger…”

“don’t rock the boat…”

“if we stop now we will impact the economy…”

and so on, and so on, and so on…

_ _ _ _ _ _

Well… where’s that booming fishing industry now…? Where’s that booming logging economy?

Where are those things that apparently “built BC…”?

And… where the heck are the salmon?

_ _ _ _ _ _

The response… (and no offence to the hard workers involved)… in British Columbia… is another multi-million dollar public inquiry involving lawyers, scientists, and know-it-alls sitting there asking the same questions… looking for the same magic bullet that is not us… some magical coincidence of ocean conditions or climate impact…

And on the other side of the equation, a slew of panels of experts, saying the same thing… “we just can’t say for sure”… “we just don’t know”… “it’s just all so uncertain”…

And the same people and institutions that were on deck to watch the sinking of the wild salmon ship… testify, trying to prove that they didn’t know what ‘sinking’ looked like… or that they believed ramming harder into the iceberg was going to right the ship… not sink it…

No one will admit that they didn’t know how to bail… or simply didn’t want to…

And anyone that suggests: “well, look at this… we harvested the crap out of them [salmon] for close to a hundred years with no respect for small or weak stocks or other species (e.g. mixed stock fisheries)… we nuked the crap out of their freshwater habitat… we are still dumping sewage and all manner of synthetic drugs and compounds into the key areas where they make their adjustments to saltwater as juveniles and freshwater as adults…

…and we’ve systematically changed the climate within a generation, which changes water flows, speeds up glacial melt, and assists in devastating habitat impacts through beetle infestations and otherwise…

and anytime any population demonstrates any sort of population blip to the positive we insist on returning to the old habit of harvesting the shit out them…

Would we treat our households this way?

Would we treat our household finances this way? (oh wait, some do… but then there’s this thing called bankruptcy…)

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

And worse yet, the institutions mandated to ensure the future of species like salmon and all of the individual runs — is basing decisions on decades old information.

For example, the numbers that guide how many Chinook should be reaching the spawning grounds in the Fraser River is based on numbers devised in the 1980s. Things have changed a little since then… there may be a few more challenges for those fish to face, so should we maybe not be getting more fish onto the spawning grounds…?

If I planned to run my household on a 1980s reality… would that make sense?

If Jack Layton of the New Democrat Party (NDP) in the current Canadian federal election ran on the same platform of as NDP leader Ed Broadbent of the 1980s — would something not seem a little off… or fishy?

_ _ _ _ _ _

Fundamental changes are required in our relationship with wild salmon…

And not one based on: how many can we catch?

The story that starts: Once upon a salmon…

…finishes with the predictable ending of a fairy tale… its just that this one isn’t a positive fairy tale ending… and it’s not a very good fish-story… more of a grim Grimm’s tale…

It generally ends in:

“when I was a kid I can remember walking across that river on the backs of salmon… there were soooo many fish, the river was alive with the sound of slapping tails and slithery, fishy movement…“

… And now, we’re lucky to see a pair of spawners…