The other day I asked how do we ? This following on the heels of the announcement by Target the huge US retail chain that it would now only carry “wild-caught” salmon as opposed to farmed salmon.

In the post I highlight the fact that around the Pacific Rim over 5 billion baby salmon are released by salmon ranching – salmon enhancement facilities. Hatcheries in other words.

Alaskan facilities release somewhere around 1.5 billion baby salmon every year – Canada releases approximately 600 million baby salmon every year. Japan releases over 2 billion – 95% of their commercially caught salmon are from salmon ranching facilities.

This is intervention at a grand scale.

There is often a lot of media surrounding Alaskan salmon fisheries. These fisheries have been “eco-certified” by the Marine Stewardship Council and they are often touted as healthy, sustainable, model fisheries.

Of course, some folks point to good ocean survival for Alaskan salmon as opposed to other stocks such as those in California, Oregon, and Washington. Other folks point to the fact that Alaska has legally mandated that fisheries can not catch over 50% of salmon runs – a more “sustainable” level than than the approximately 80% that Fisheries and Oceans Canada allows their fisheries to take from salmon runs (Maximum Sustainable Yield).

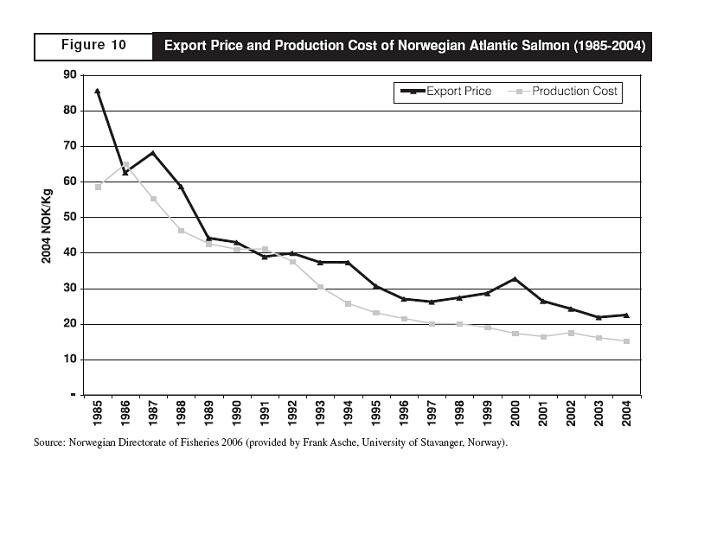

These factors may all contribute – however, I might point to a worrisome trend of more hatchery fish contributing to fisheries. This graph is from by Gunnar Knapp, and Cathy Roheim and James Anderson:

Alaska has approximately 40 hatcheries. Canada- British Columbia has almost 200.

Alaska has approximately 40 hatcheries. Canada- British Columbia has almost 200.

One of the concerns with hatcheries is that they reduce the genetic diversity of salmon runs. Genetic diversity in any species suggests a more hearty species able to withstand various threats and changes.

Alaska may be pumping out more baby salmon than BC – which requires immense amount of feed for those baby salmon while they are still in hatcheries – as well as eating natural feed in the North Pacific. However, Canada is pumping out baby salmon from way more facilities which might suggest a wider threat to genetic diversity over a wider geographic area.

In 2005, Xanthippe Augerot and the State of the Salmon Consortium produced an

It’s a great book and a very affordable price for it’s coffee table book size and endless color maps.

One of the maps shows all of the hatcheries around the North Pacific (you can view a much larger version ):

That’s Japan leading the pack with 378.

British Columbia is second with 191.

And Washington with 88.

Hatcheries are not a new intervention. In the 1902 Canada Fisheries Report I quoted in an earlier post – – there is a report on the total amount of fish released from hatcheries across the country. Here is the B.C. summary:

Between 1885 and 1900 BC hatcheries sent out over 100 million baby salmon into the North Pacific.

Between 1885 and 1900 BC hatcheries sent out over 100 million baby salmon into the North Pacific.

If you had a chance to read the post – this full 430 page report also reported that Fraser River canneries canned over 30 million sockeye that year and could have canned another 30 million if the hatcheries had had more capacity.

So why the hell were governments spending money on hatcheries?

Maybe these quotes from the report might shed some light:

Trout devour other species, and even make war upon each other. It is no doubt impossible in most salmon rivers to exterminate the trout, or prevent their inroads; but every means should be taken to keep their numbers down and successfully check their super-abundance.

This idea of “super-abundance” is still alive and well in fisheries management plans. There is a term in salmon management called “over-escapement”. Salmon that “escape” fisheries and reach the spawning grounds are called “escapement” – rather than spawners.

As I have asked before are we managing for the fish – or are we managing for the fisheries?

This idea of over-escapement permeates institutions and has been adopted by many. If too many salmon are allowed to reach spawning grounds they will kill each other, dig each others eggs, rampant diseases will ensue – thus we better intervene and catch as many as possible.

Gee, as far as I know salmon have been around a few million years – they’ve done a pretty decent job of managing themselves. And funny enough, before western science and fisheries management and canneries and open ocean fisheries arrived – salmon and humans were doing pretty well together.

Maybe this quote from the 1902 report also still permeates salmon management:

While, of course, the department is competent to decide, more so, indeed, than any local authorities, such matters as these, on account of the extensive and varied means of information it possesses…

Yes, of course, indeed…. what the heck would local authorities and individuals know about salmon?

And, maybe this paragraph points to an attitude that still permeates institutional salmon management:

A salmon river should, as far as possible, be a river for salmon, and no step should be neglected to make it so. On the other hand a trout stream is not to be despised; but a trout stream should be a stream for trout, a stream that is to say, in which every encouragement for their increase and welfare, and every protection against injury and depletion is afforded them. It is justifiable in a good trout stream to exclude and destroy salmon for, as that most enthusiastic of trout culturists, the late Sir James Gibson Maitland once declared,—” trout are most destructive to salmon spawn”…