This is not one of those red-neck leaning commentaries on First Nation organizations — this is directed at the many shoes that must drop at the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). This is also a commentary based on some pro bono work I do for a First Nation community in an ‘isolated’ area of British Columbia. And some commentary on the challenges of politics, deal-brokering, and negotiations that involve healthy day rates, many jet flights, and endless per diems — that will continue to stifle actual progress, actual implementation, and real “action” (not plans for action – as in “Action Plans”).

National Geographic

At the same time, it’s not to take away from places where good work is being done, where some results can actually be demonstrated, and relationships are changing for the better.(I’d be happy to hear about these…)

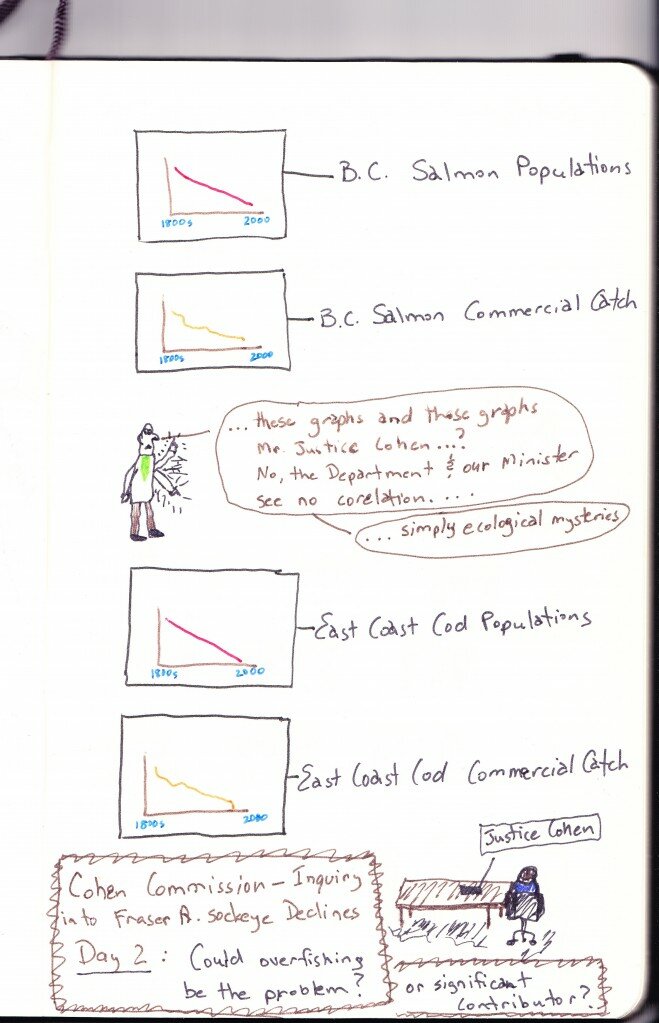

The aboriginal organization I attempt to assist straddles a fascinating part of the Province; they have part of their territory in the Fraser watershed, part of their territory in the Skeena watershed, and part of their territory in the Arctic (Peace/Mackenzie River drainage). The once huge sockeye runs that spawned in the upper Fraser watershed, are going the way of North-Atlantic Cod; and thus this community is left to catch their food fish (for a community several hours from the nearest paved road and grocery store) in the headwaters of the Skeena watershed (a long journey from the main community).

(Sturgeon in the Fraser, and specifically in this area, are already parallel with North-Atlantic cod…)

In the Arctic drainage portion of their territory, fish such as grayling and rainbow trout have been heavily impacted by that fine engineering feat: WAC Bennett Dam and 350+km long Williston Reservoir downstream — the same body of water that has a fish advisory suggesting only one fish a year is suitable to eat (due to significant levels of mercury – natural leaching and from the trees that were never logged prior to flooding).

Throw in the apparent benefit of over a hundred years of placer mining for gold (when a stream bed is turned upside down and hosed out to find gold nuggets), multiple decades of logging, and now the scourge of online mineral staking and mineral exploration.

Twenty minutes from the main community is a 1940s mining relic — a mercury mine that has never been properly cleaned up and still leaches mercury into the surrounding environment. The same road that accesses the old mine is now used by another mineral exploration company with a large, active drilling program zeroing in on a potentially large copper-gold deposit.

In the community itself, cancer rates and other illnesses — e.g. diabetes, strains of which are now being linked directly to Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) like PCBs and other chemicals that exist for a long time and build up in food chains — exist at scarily-high rates.

_ _ _ _ _

A visit to Fisheries and Oceans Canada website: shows all of the planned annual transfer payments to various programs over the next few years. Within the Fisheries and Aquaculture Management program there are a variety of programs with upcoming annual transfer payments. For example the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy (a program in existence since 1992 following the Sparrow decision in the Supreme Court of Canada) will have transfer payments of approximately $32.3 million each year.

The Aboriginal Aquatic Resources and Ocean Management (AAROM) program — which funds aboriginal coalition or collaborative organizations — will have transfer payments of almost $14 million per year. Part of this program includes license buy-backs in the commercial sector.

The Pacific Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiative (PICFI) will have transfer payments of approximately $35.5 million. Parts of this are also commercial license buy-backs.

Other programs of note: the Pacific Salmon Foundation will receive close to $1 million; the Fraser Basin Initiative $1.1 million; and the Maa-Nulth treaty settlement (west coast of Vancouver Island) $3.4 million.

Rough total for transfer payments related to Pacific salmon management: just under $90 million per year.

This does not include DFO staff costs – of which if you’ve seen earlier posts – on the Draft 2010 Integrated Fisheries Management Plans (IFMPs) close to 100 staff are listed as contacts in relation to these plans. And thus could we say on the very, very low end each of those staff cost about $100,000 each when one adds in wages, benefits, employer costs, and travel. Is my math right to suggest that’s about $10 million? (on the very, very low end. Travel adds up in a hurry. For example, for me to attend two days of meetings in Kamloops, BC traveling from Prince George, BC is easily over $1000 a pop in travel and meal costs alone. I was at meetings recently where DFO showed up with 13 staff members to a meeting where 2 would have sufficed).

What’s my point here?

Have you seen my post (it appears to be rather popular) —

Last year the landed value of wild salmon was only $20 million.

Are there some imbalances at work here….?

_ _ _ _ _

And how much does this aboriginal organization I do research for receive in Fisheries funding?

$0

This organization is part of a tribal council that receives approximately $300,000 in funding from fisheries — however this is largely project-based funding, with a focus on counting fish (enumeration). Plus this tribal council represents approximately 6 different communities in its fisheries work, so that the $300,000 does not go far. Probably pays for about two staff members and some sporadic project funding — this across a substantial geographic area and is only focussed on the Fraser River watershed.

So where is the $90 million or so of funding going?

And what happens when there’s no more salmon to count? Will DFO then actually begin doing habitat restoration work?

_ _ _ _ _

One is left asking — are there any evaluations of these programs?

In a :

The evaluation concludes that the AFS assists DFO to manage fisheries in a manner consistent with the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Sparrow and subsequent decisions. The AFS also relates directly to DFO’s strategic outcome of Sustainable Fisheries and Aquaculture.

The relevance of AFS to the public interest is amply demonstrated in that the AFS works to build stronger relationships and improve the quality of life of Aboriginal peoples in Canada, and facilitates the participation of Aboriginal peoples in modern fishing and aquatic resource management.

These statements are made early in the paper, and yet when one reads to find any substance to these claims, for example, for an isolated community that received absolutely zero funding even though they straddle three major watersheds. Apparently there is a process of DFO evaluation called: Results-based Management and Accountability Framework (RMAF).

A RMAF was developed for the AFS in 2003, providing a strategy for measuring the performance of the AFS through the identification of expected outcomes. The RMAF also identified the data requirements that were to be used to assess the achievement of the expected results of the Program. The formative evaluation team encountered a number of challenges that affected its ability to assess achievement of the AFS program’s expected outcomes.

…The data required to support the outcomes and performance indicators was not collected in a systematic manner that would allow for the RMAF to be used as an effective management tool. The evaluation also found that some outcomes and indicators identified in the RMAF may no longer be relevant and need to be validated. In addition, accountability for data collection had not been effectively assigned…

…A second challenge was that a planned national database had not been implemented at the time of the evaluation….

…A third challenge was that the quality of reporting from some Aboriginal groups, especially those with smaller agreements, was either weak or absent in many instances…

In other words, in 15 years of the program by the time of this evaluation — and 4 years of a renewed program certain basic evaluation tools were never put in place. That makes sense at over $30 million per year:

“The relevance of AFS to the public interest is amply demonstrated”

… is that so?

_ _ _ _ _

The Aboriginal Aquatic Resources and Ocean Management (AAROM) program isn’t any better.

In a of the program was released by DFO.

AAROM was a 5-year contribution program from 2004-05 to 2008-09. Participation in this program was voluntary and the funding totalled $51.0M over five years.

The internal evaluation found that this program ran pretty ad hoc and loose:

Effectiveness

A Performance Measurement Strategy, that identified expected results as well as the indicators and data collection methodology to assess them, had been prepared for AAROM. The strategy, however, was not fully implemented. Individuals involved in the program explained the successes of the program, however, much of this is based on anecdotal information and not on concrete reliable performance information.

Success of this $51 million program is based on anecdotal information?

Wow…

It gets even better – and remember this is an internal evaluation…fishy folks investigating fishy folks:

At the time that AAROM was implemented in 2004, a Results-based Management and Accountability Framework (RMAF) was prepared for the program. The RMAF included a performance measurement strategy (PMS) for the program. This strategy was never implemented.

While the RMAF set out criteria for assessing the program, the information needed was unavailable as this had either not been collected or where collected, it had not been consolidated in a manner to allow for program assessment.

The Aboriginal Policy and Governance Directorate (APG) had planned to implement a database that would capture key information that would measure the performance of the program. This database has not been put in place and remained under development at the time of the evaluation.

[still in development 5 years into the program? are you kidding me?]

The non-implementation of the the PMS and the absence of the database to accumulate performance information limited the evaluation team’s ability to fully assess the program.

So how the heck does anyone know these multi-million dollar programs are doing anything effectively…?

_ _ _ _ _

Is it time for third-party management of DFO?

Maybe more folks with business backgrounds and a little less fishy experience?

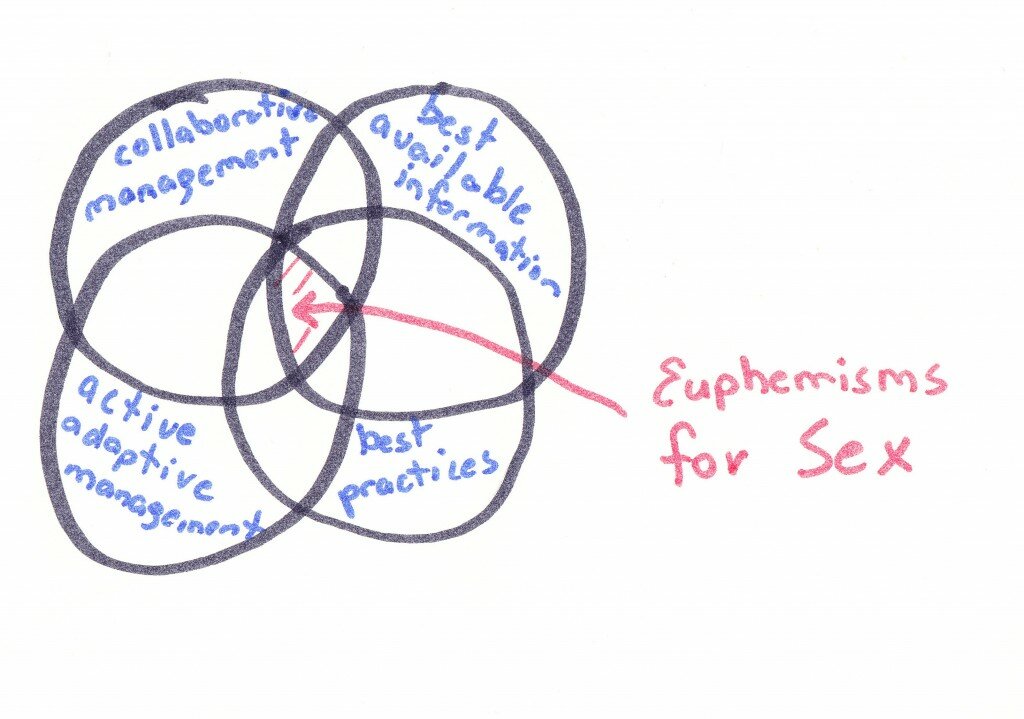

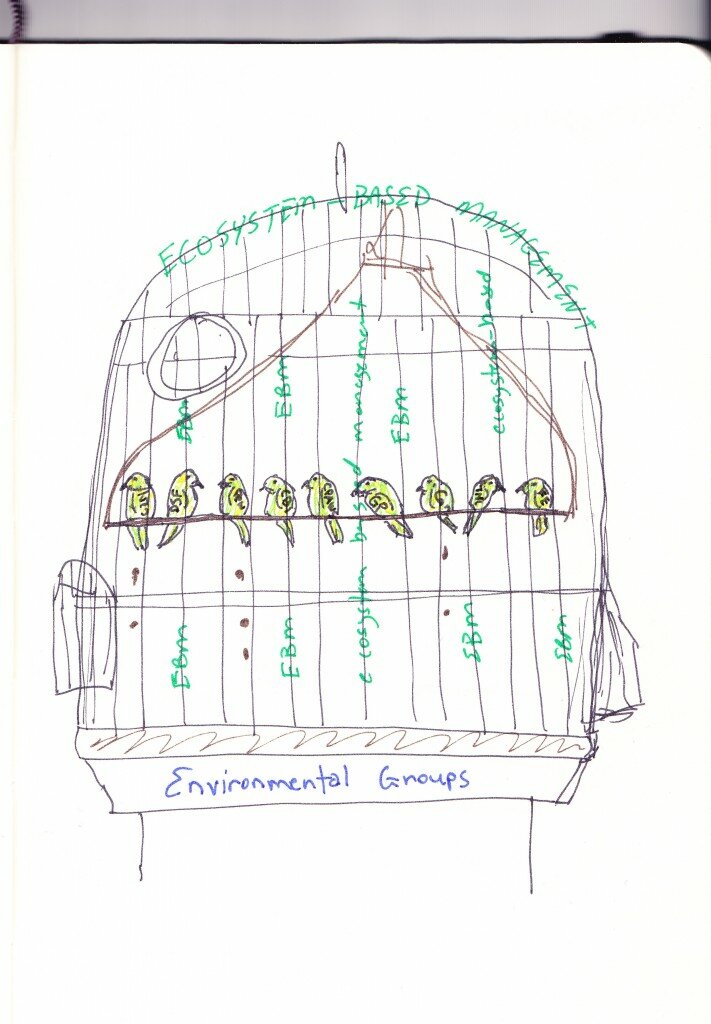

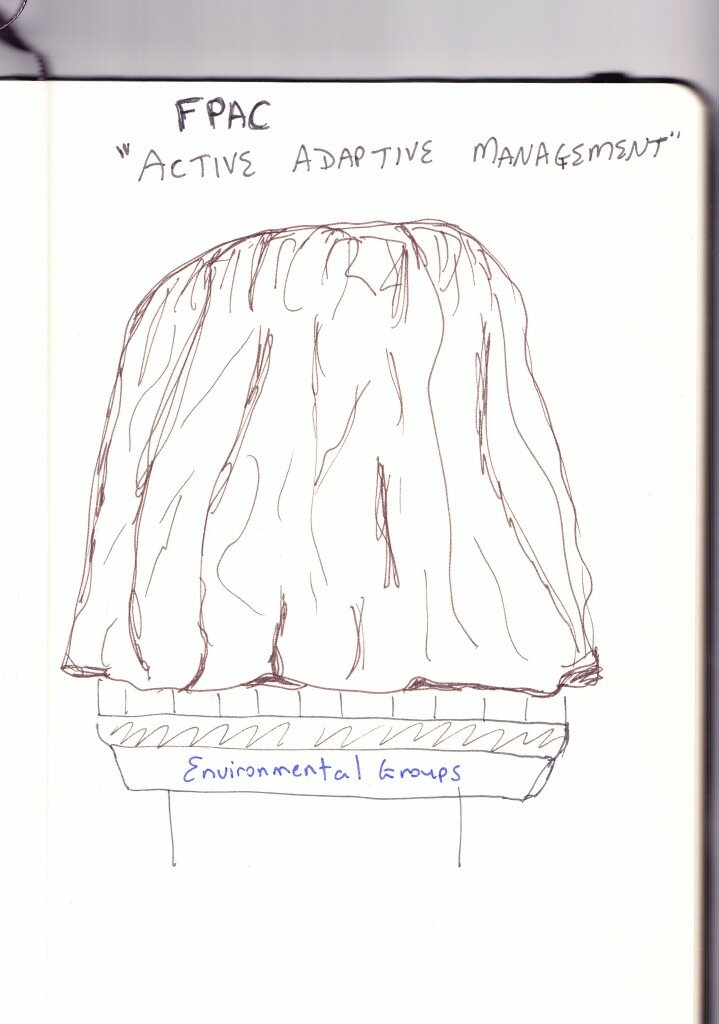

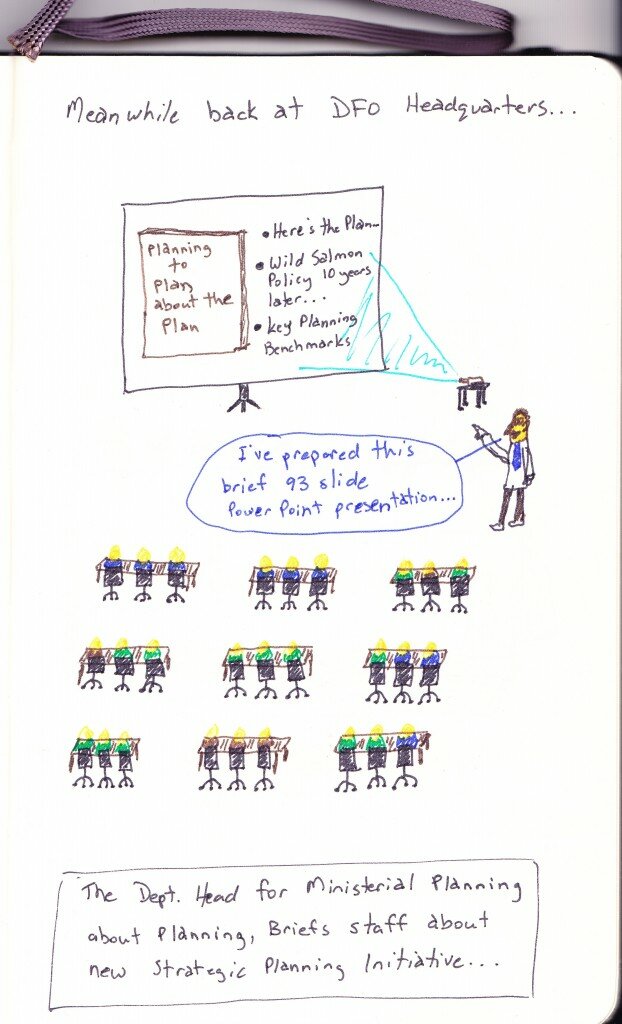

Thursday evening, I drove back from Kamloops, British Columbia following two days of meetings that included Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) staff. As per usual, for almost any comment made, or criticism suggested, DFO bureaucrats have a bafflegab filled response. There’s a whole lot of “at the end of the day…” & “change doesn’t happen over night…” & “we care…” & “we are considering your input…” and so on,and so on.

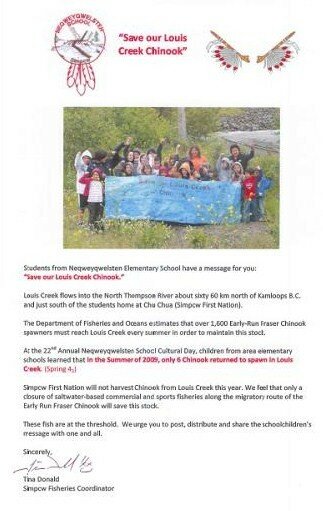

Thursday evening, I drove back from Kamloops, British Columbia following two days of meetings that included Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) staff. As per usual, for almost any comment made, or criticism suggested, DFO bureaucrats have a bafflegab filled response. There’s a whole lot of “at the end of the day…” & “change doesn’t happen over night…” & “we care…” & “we are considering your input…” and so on,and so on. Here’s a link to the document for a better view of this important message.

Here’s a link to the document for a better view of this important message.