This headline from the Seattle Times Local News the other day (photo credit: Astrid Van Ginneken):

The article states:

During the summers of 2004-08, scientists tracked the J, K and L pods of orcas (also known as killer whales) in the western end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and San Juan Islands, to learn what they were eating and analyze where their food came from. No easy task, the work involved following the orcas in small boats and gathering killer-whale excrement and regurgitation, fish scales and other tissue with a fine mesh net after the whales ate.

Examination of the material, including DNA testing, revealed that the orcas select chinook salmon nearly exclusively for food, despite far more abundant numbers of pink and sockeye in the area at the same time.

“They would literally knock pink salmon out of the way to take a chinook,” said Brad Hanson, biologist with the National Marine Fisheries Service Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle, and lead author of the paper, published last month in the online journal Endangered Species Research.

Scientists took their examination a step further, to learn by DNA analysis where the fish came from. Of the chinook salmon sampled, 80 to 90 percent were from British Columbia’s Fraser River, and only 6 to 14 percent from Puget Sound-area rivers.

…

“It certainly has raised the question of providing suitable numbers of chinook available to sustain their current needs, both in the U.S. and Canada,” Ford said.

The full study is available online from the March 2010 edition of the journal Endangered Species Research:

Some pieces that stood out for me on initial reading:

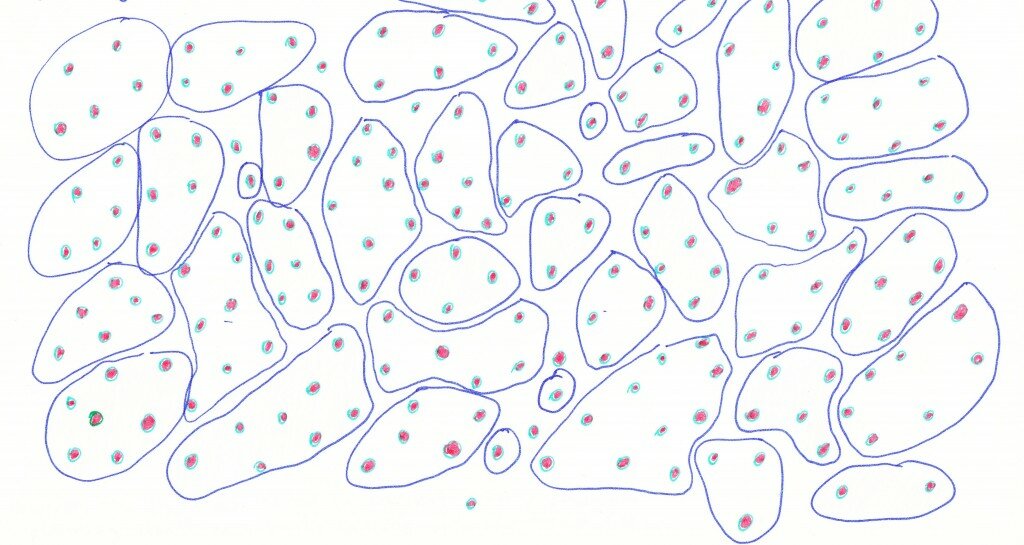

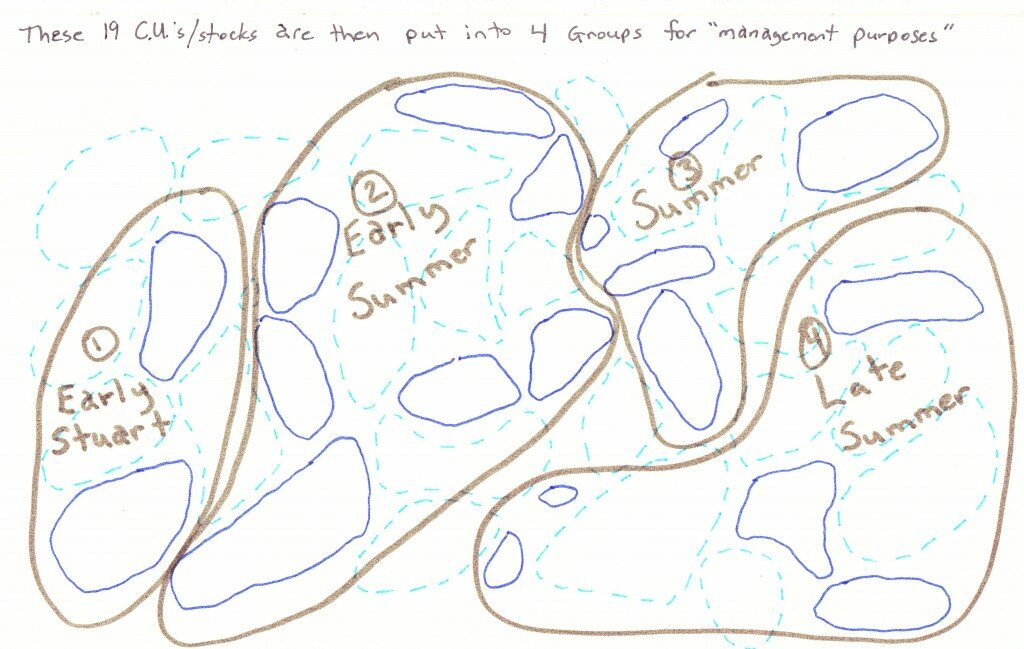

… in May and June, the Fraser River stocks in the prey samples were dominated by stocks from the upper portion of the watershed. In July and August, stocks from the central portion of the watershed were most common, while in September the predominant Fraser River stocks were from the lower watershed, a pattern consistent with the seasonal distribution of the major Fraser River Chinook salmon stocks as they enter the river mouth

And here’s the telling piece:

If Chinook salmon constitute the bulk of these whales’ diet, then fish managers will need to take this information into account when managing Chinook salmon fisheries and conservation efforts (NMFS 2008a).

The NMFS is the National Marine Fisheries Service of the U.S. I’m not sure if the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans chats with the NMFS…

Currently, on the Fraser River — and in particular the upper Fraser River stocks that endangered orcas hit in May and June — there is not only a “conservation” concern but an extinction concern. These Chinook are referred to as the Early Spring Chinook or specifically the 4 sub 2 population of Chinook. The “sub 2” referring to the time that these Chinook spend in fresh water as babies before heading to the ocean, the four referring to years old.

Last year on the Thompson River (major tributary to the Fraser), and specifically the Nicola River, were record lows:

-

- 26 Chinook returned to the Coldwater River

- 138 Chinook returned to Spius Creek (which has a hatchery)

- 461 Chinook returned to the Nicola spawning grounds

Estimates suggest that for any fisheries to occur these populations need:

-

- 2000 Chinook returning to Coldwater

- 2000 to Spius; and

- 6000 to the Nicola.

This year, the pre-season Integrated Fisheries Management Plan put out by Fisheries and Oceans (of which you can comment on until April 26 <>) is forecasting “Returns of Spring 4(2) Chinook in 2010 will come primarily from a parent generation of 10,637 spawners in 2006.”

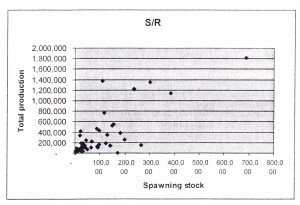

Thus, we can assume that the hope is that the spawners that return this year will be at least equal to the 10,000 that spawned in 2006.

Yet, as DFO states in their 2010 Draft Salmon Outlook (vers. 4 Jan. 18, 2010):

“2009 was the fourth successive year where recruitment failed to replace parental spawning abundance”

In the 2010 Salmon Outlook, Spring 4(2) Chinook has been classified as a “stock of concern given poor survival rates and very poor spawning escapements in recent years.” On a scale of 1 to 4, with 1 being the worst — the Spring 4 (2) Chinook are a “1”:

Stock is (or is forecast to be) less than 25% of target or is declining rapidly. Directed fisheries are unlikely and there may be a requirement to avoid indirect catch of the stock.

And so this year these Early Spring Chinook are most likely going to see returns far below the 10,000 required to allow any fisheries.

And yet, sport fisheries for Chinook remain open coastwide in B.C. — including Strait of Georgia, Juan de Fuca and Johnstone Strait.

Now add in the fact that endangered Orcas in the Salish Sea (Strait of Georgia) and Juan de Fuca rely heavily on Fraser Chinook and the US National Marine Fisheries Service has suggested that: “fish managers will need to take this information into account when managing Chinook salmon fisheries and conservation efforts.”

Some folks who suggest seal culling is in order (even though studies suggest salmon comprise a small portion of their diet) — may start suggesting that the orcas have got to go (with studies suggesting that salmon, specifically Fraser Chinook comprise a huge portion of their diet).

Or… Or, maybe we could do a better job of dealing with things that we can actually control… ummm, like ourselves.

Should there really be any fisheries open right now that may catch Early Spring Chinook – when populations have been unable to replace themselves (even one hatchery supported population)?

First Nations up and down the Fraser River are calling for full closures — including their own food fisheries — especially the Nicola Tribal Council as these Early Spring Chinook spawn in their Traditional Territories.

No commercial fisheries are planned that may catch these Early Spring Chinook — and yet, sport fisheries remain open.

Without even getting into the legal requirements of Fisheries and Oceans (and the federal government) to ensure First Nations food, social and ceremonial requirements are met before any fisheries are open — It still must be asked whether sport fisheries should be open?

Why is DFO refusing to close these fisheries despite all the evidence that suggests full closures are essential — not only to ensure continued existence of these Chinook runs, but also supporting endangered Orcas?

These early-timed Chinook can not afford economic and political decisions — nor, can endangered Orcas.

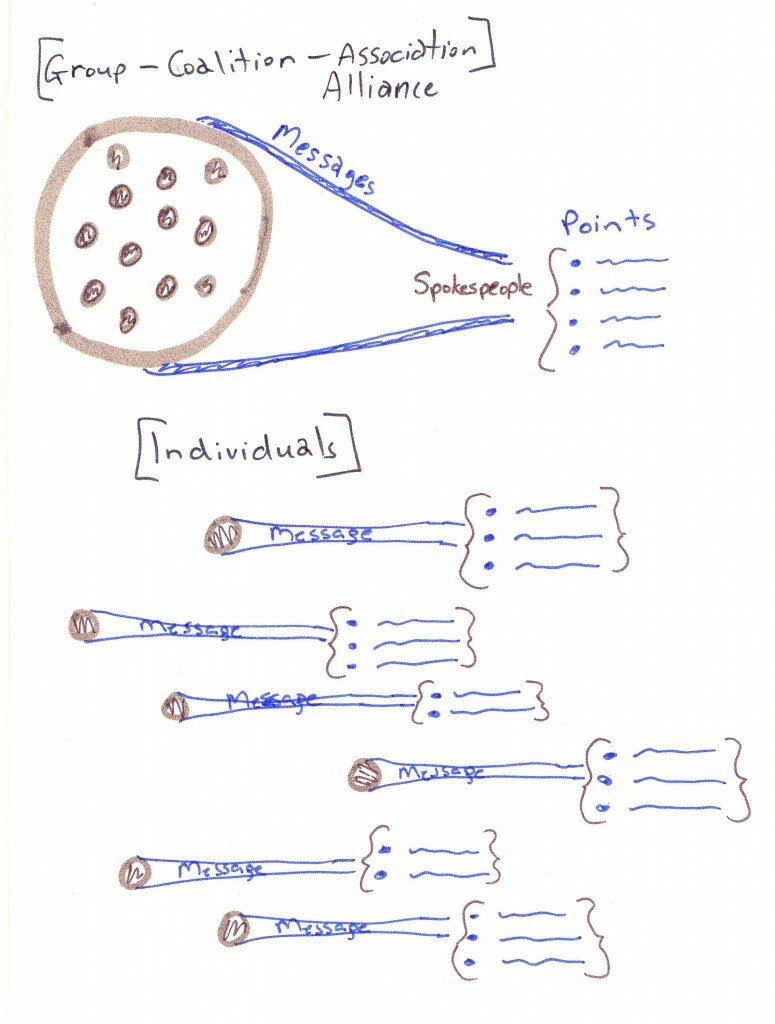

Henri Tajfel developed the “” with his colleague John Turner in the early 1970s. The theory suggests that people have a range of identities — from personal through social. The social range often distinguishes itself through identifying with a particular group. Folks generally identify themselves with a group through four elements: categorization, identification, comparison, and psychological distinctiveness.

Henri Tajfel developed the “” with his colleague John Turner in the early 1970s. The theory suggests that people have a range of identities — from personal through social. The social range often distinguishes itself through identifying with a particular group. Folks generally identify themselves with a group through four elements: categorization, identification, comparison, and psychological distinctiveness.