Seth Godin, marketing guru and general ponderer, has a fitting post today on — and many folks might consider pondering the message. Here are a couple key points:

An organization with eight people in it might be happy, profitable and growing. The same business with twenty might be on the way to bankruptcy.

Ideas, markets, niches and causes have a natural scale. If you get it right, you can thrive for a long time. Overdo it and you stress the inputs…

Your industry might have room for six or seven well-paid consultants, but when you try to scale up to 30 or 40 people on your team, you discover that it stresses the market’s ability to pay.

Yesterday, my website was picked up by a British Columbia that is focusing on the issue of potential sport fishing closures to protect the (the 4-2’s). If you haven’t seen earlier on my site here, or seen the numbers, this particular population of Fraser Chinook is on a death spiral and has been for several years (over four years by Fisheries and Oceans own estimates).

Right now, these Chinook are also migrating from the North Pacific to the Fraser River. At this moment, they are migrating right past the BC capital city of Victoria through the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

And, yet Fisheries and Oceans Canada has deemed that Chinook stocks around British Columbia are healthy enough to support coast-wide sport fishing openings on the ocean — from Haida Gwaii to the mouth of the Fraser River.

However, First Nations and others are asking for a complete fishing closure to allow these early-timed Chinook through to the spawning grounds of which basically every last fish of these runs needs to finish their life. Scarier yet, there is even a major hatchery (Spius Creek) that support this early-timed Chinook run — and the run is still in deep trouble.

Reading through the particular Sport Fishing discussion forum — one can see that many individuals are taking serious issue with the fact that sport fishing openings that they rely on for their businesses may have to be closed — and should be closed based on the early-timed Chinook numbers. Angry individuals are lashing out at targets for their blame — and fair enough, many of these folks have probably run thriving businesses for several years based on a finite resource.

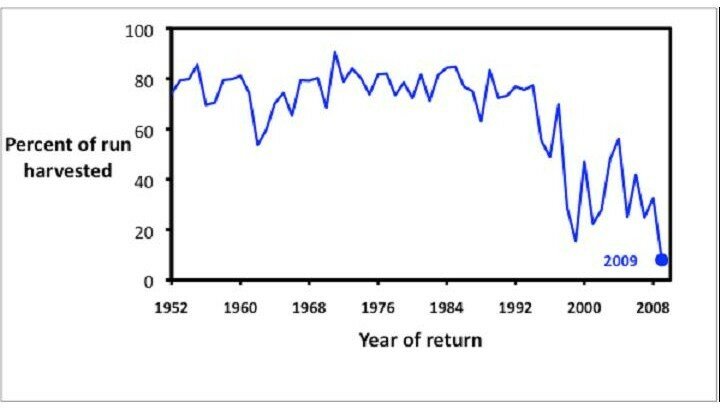

One thing is clear… numbers and statistics coming out of Fisheries and Oceans are unreliable, full of holes, and dependent on various computer models and equations. DFO’s own numbers suggest that early-timed Chinook can only sustain an exploitation rate of 8-11% while productivity remains as low as it has been for over four years. Last year (2009), DFO numbers just released suggest that 50% of the run was killed (with 30% of that attributed to two marine sport fishery areas).

(It should be pointed out that the south-east Alaska commercial fishery is allocated a certain percentage of Chinook as part of the Pacific Salmon Treaty. Of course, DFO maintains that all of these early-timed Chinook migrate along the continental shelf before coming inland and thus don’t impact Fraser Chinook)

(oh yeah, that’s out where the Pacific Hake trawl fleet is busy, along with other industrial trawl fisheries… just fish for thought).

Varying levels of accuracy or not — 50% of the run killed is absolutely unacceptable. It doesn’t even matter at this point who caught what percentage. The bottom line is that DFO is failing miserably in protecting a vital public resource that countless individuals (and other critters) depend on.

And worse yet, this massive federal bureaucracy with over one hundred people responsible for looking after wild salmon maintains ignorance:

- “we don’t know what it is…”

- “ocean productivity is down… it’s not us.”

- “it’s definitely not salmon farms…”

It is, thus, unfortunate, to read various discussion postings, comments on media stories and so on, that point fingers at First Nation fisheries as the culprit — or carry on about equal access for all, or “one fishery for all” as the federal Conservatives call it.

Quick numbers: historically the commercial fishery is responsible for over 90% of salmon catch in BC, sport fishery 3-5% and First Nation fisheries 3-5%.

As Godin, suggests in his post:

An organization with eight people in it might be happy, profitable and growing. The same business with twenty might be on the way to bankruptcy.

I draw an analogy with the U.S. banking sector and what has happened over the last few years. For many years the banking sector was ‘happy, profitable and growing’. Then it got carried away and when that particular business sector reached “twenty” — bankruptcies ensued en-masse.

The difference with wild salmon… there are no “Tarps”.

Troubled Asset Relief Programs (TARP). And even if there was — interventions are incredibly expensive; just ask the Alaskan or Japanese salmon ranching programs…

Over the last decade or two, the sport fishing sector has grown on a scale similar to fish farming — somewhere around 2000%. (Actually, fish farming since the 80s is probably closer to a growth rate.)

When I was a kid growing up on Haida Gwaii (once referred to as the Queen Charlotte Is.) sport fishing as a business was a tiny sector. It’s not to say that lots of folks weren’t sport fishing. I was on a river or on the “chuck” (ocean) basically every weekend from the age of 3 to late teens — mainly fishing for coho.

Sport fishing lodges and the like were just not a huge business — yet.

Now… sport fishing lodges on the west coast of Canada are booming businesses — dotting the BC coast like the salmon canneries and whale stations of old. Or, the logging camps of past decades. (do you sense a pattern?)

Along with this corporate consolidation, tonnes of small mom-and-pop sport fishing businesses; eking out a living on a seasonal sport fishing clientele.

Curiously, it seems to be a similar tract as the commercial fishing industry (or whaling industry before that) — which has largely gone the way of the U.S. banking sector. Only the big and ‘vertically-horizontally integrated/ corporately consolidated‘ have survived. Most of the mom-and-pop operations (i.e. like small regional banks) driven out of existence.

Exactly as Godin suggests:

Ideas, markets, niches and causes have a natural scale. If you get it right, you can thrive for a long time. Overdo it and you stress the inputs…

Sport fishing and sport fishing businesses relying on wild salmon (or hatchery salmon) also have a natural scale — just as commercial fisheries do. There may be room for several businesses built upon the backs of wild salmon; however there is not room for corporate concentration and consolidation.

There is not room for rough estimates that suggest:

- a peak day off the west coast of Haida Gwaii with 400-500 sport fishing boats in the water;

- off the Northwest Coast, West Coast, and southwest coast of Vancouver Island with maybe 1000 (?) sport fishing boats in the water;

- Johnston Strait and Georgia Strait with 200-400 (?) boats;

- Central BC Coast with ?? hundred;

- allocations of Chinook to the Southeast Alaska commercial fishery; and so on.

Godin:

Your industry might have room for six or seven well-paid consultants, but when you try to scale up to 30 or 40 people on your team, you discover that it stresses the market’s ability to pay.

I would hope then — and as an avid sport fisherman myself — that maybe the sport fishing business sector and associations might enter those tough discussions about “scale”…. about how many ‘businesses’, along with how many ‘food fishers’ (my general focus for sport fishing) can be supported by current salmon runs in B.C.

Maybe go have some discussions with sport fishers and sport fishing business-owners along the coasts of Washington, Oregon, and California who haven’t seen an opening in a little while… with any openings almost entirely focussed on hatchery runs.

We all need to remember that we’re basically after the same thing: salmon. Sadly, of which, are declining at rapid rates and have been for at least my generation.

And, of which, we’re not the only ones that depend on them — as demonstrated in my picture above.