I think there might be a cake in the works (I’ve included a mold to bake it in). Some evidence of this can be seen in to Victoria to protest the impact of salmon farming on BC’s wild salmon, recent court cases that have found Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) is failing in their responsibilities, and a variety of other factors.

I think there might be a cake in the works (I’ve included a mold to bake it in). Some evidence of this can be seen in to Victoria to protest the impact of salmon farming on BC’s wild salmon, recent court cases that have found Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) is failing in their responsibilities, and a variety of other factors.

As a follow-up to on the current denial stage surrounding B.C. wild salmon, and the post from Saturday: which was a follow-up post to early March: — I am curious whether a non-confidence vote is brewing?

www.spruceroots.org

This idea is not a new idea. In early 2001 on Haida Gwaii (formerly referred to as the Queen Charlotte Is.) close to 20% of the adult population of the islands marched on to the British Columbia Ministry of Forests office and filed a vote of non-confidence. Over 600 ballots were cast that day and marched to the doors of the Ministry. (click the picture to read story).

[If you can’t read the placard it states: “MOF You’ve taken everything but the Kitchen Sink“]

The red stumps are part of the “Red Stump Brigade” which can still be found stuck into the ground near various Haida Gwaii driveways.

As John Vaillant suggests in his good read of a book: “The Golden Spruce: A True story of Myth, Madness, and Greed“:

“Out in Haida Gwaii, the rain keeps most fires at bay and coastal timber is far less susceptible to bug infestations that are devastating the interior. It is humans and things they carry with them that remain the greatest threat to the islands. A terrible irony is that, philosophically, Hadwin was in sync with much of the local population: in December 2000 an interracial group of islanders staged a protest — essentially, a no-confidence vote — against the Ministry of Forest’s handling of logging in the islands. There hadn’t been a demonstration of that kind in a decade, and this one was the biggest ever: 20 percent of the islands’ adult population participated. Since then there have been some striking changes not just in the way logging is practiced but in the status of the islands themselves.”

The irony that Vaillant is referring to is that “Hadwin” — Grant Hadwin — is the individual who cut down the revered Golden Spruce (an incredibly rare tree, the only one of its kind on Haida Gwaii) in early 1997. He was trying to make a statement against industrial logging. Hadwin disappeared off the coast of BC not long after the incident.

It was a twisted approach to protest…however… is it all that different than suggesting that farming salmon in open-net pens on wild salmon migration routes is a good way to protect wild salmon?

1. One half cup of not knowing one’s percentages very well.

The 2009 DFO Integrated Salmon Management Plan – last season – listed Fraser River early-timed Chinook as a “stock of concern” with the following conservation objective: “to implement management actions that will reduce the exploitation rate approximately 50% relative to the 2006 [33.9%] to 2007 [54.4%] period.” This means the objective was to reduce exploitation to approximately 22% (half of average [44.2%] of 06 and 07).

- Estimates just out from DFO suggest exploitation rate last year (2009) on early-timed Chinook were 48.7%. Not only did they not reduce by half — exploitation was actually almost 5% higher than the average.

(Disclaimer: this might actually be one cup, as opposed to 50% of one cup, or it might be two cups – hard to know when percentages are so confusing and which Ministry is measuring)

2. One overflowing cup of very effective lobby efforts in Ottawa

DFO’s own numbers suggest that exploitation rates on early-timed Chinook need to be 8-11% during times of low productivity like we are experiencing right now, and have seen for at least the last four years. Last year, the ocean sport fishery in Juan de Fuca alone — is estimated to have caught almost 12% of the Chinook destined for the Nicola river. This means this particular sport fishery alone is catching what DFO deems sustainable for the entire population.

- Local estimates suggest that on peak fishing days there are well over 500 (maybe closer to 800) sport fishing boats in Juan de Fuca (from Victoria, B.C. up the Vancouver Island coast to Port Renfrew).

- The Chinook sport fishery is open coast-wide in BC right now, despite terrible forecasts for this coming year and terrible returns of early-timed Chinook over the last four years.

3. Two cups of not being able to follow your own “recipe”

DFO’s Wild Salmon Policy explicitly defines what is meant by Conservation — the primary goal of salmon management:

Conservation is the protection, maintenance, and rehabilitation of genetic diversity, species, and ecosystems to sustain biodiversity and the continuance of evolutionary and natural production processes.

This definition identifies the primacy of conservation over use, and separates issues associated with constraints on use from allocation and priority amongst users.

Yet, when it comes to Fraser early-timed Chinook there are no conservation goals — only percentages attached to ‘constraints on use‘ as demonstrated in the statement: “to implement management actions that will reduce the exploitation rate approximately 50% relative to 2006 to 2007.” This is not a conservation goal, this is a constraint on use – which, coincidentally, was failed upon miserably; placing Nicola River Chinook (i.e. early-timed Chinook) on extinction watch.

4. A good dose of completely flawed computer simulation model based on less than 10% of a population.

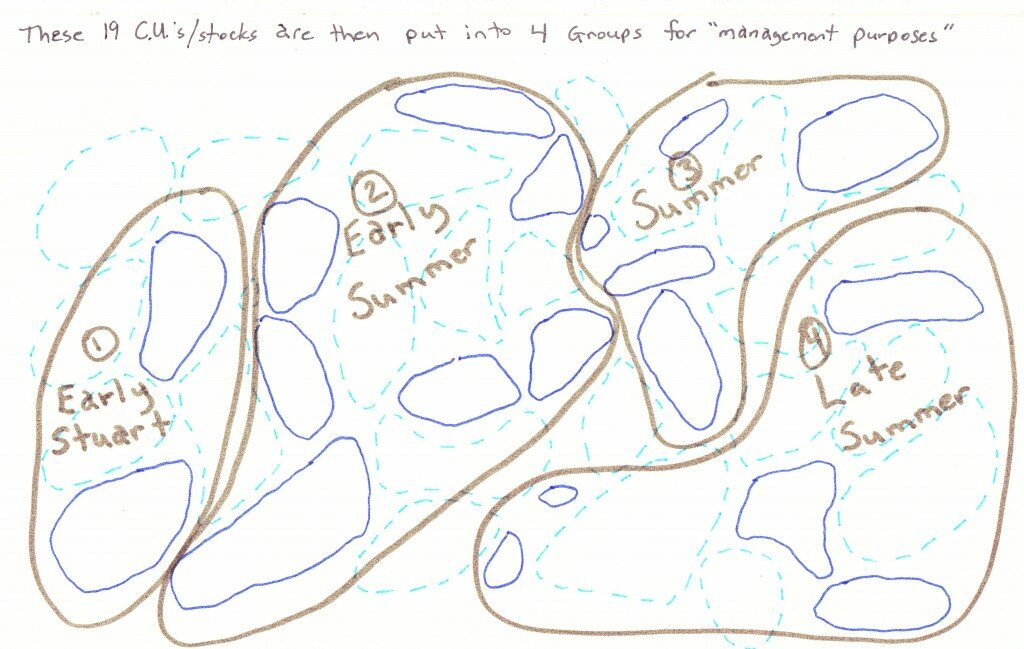

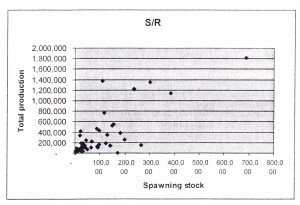

See posts regarding Fraser River Spawning Sockeye Initiative (FRSSI). FRSSI simulates Fraser River sockeye populations based on — despite there being over 200 separate Fraser sockeye stocks.

This model is like trying to make a cake and only using 10% of the ingredients and then wondering why the heck the cake didn’t turn out as expected — or collapsed like a rusty lawn chair…

5. Three litres of very flawed economics, budget planning, and misuse of funds.

See post:

Further evidence? I was at a meeting late last week of approximately 50-60 people discussing DFO’s pre-season planning. When it came time to give DFO feedback they showed up at the meeting with 13 staff. That’s right, 13 staff when 2-3 would have sufficed. Many of these staff had taken at least two flights to get to the meeting, rented cars, and were there for two days staying in some hotel. What’s the estimated cost of that type of frivolous spending?

Directions for Mixing and Baking:

Bake these ingredients in a bureaucratic malaise of about 10,000 employees, an east coast Minister with a distinguished career in Revenue Canada, and decades of Royal Commissions, public inquiries, and Auditor General reports.

Suggested icing?

Lemon-Inaction Glaze (for enhanced tartness)

(Future recipes to come…)

This is not meant to be a joke, but it may end that way.

This is not meant to be a joke, but it may end that way. Wow, I didn’t realize it was this simple. I’ll keep my eyes open for the next issue of Consumer Reports that reviews Fraser River sockeye escapement strategies…

Wow, I didn’t realize it was this simple. I’ll keep my eyes open for the next issue of Consumer Reports that reviews Fraser River sockeye escapement strategies…