Yesterday, I posted on — largely in relation to the outcomes of the Supreme Court of British Columbia decision or Nuu-chah-nulth decision regarding fisheries rights. In essence, the courts ruled that the Nuu-chah-nulth have an aboriginal right to sell fish commercially – which flies in the face of limiting First Nation fisheries to strictly “food, ceremonial and social purposes.”

Not only do the Nuu-chah-Nulth have the right to sell fish commercially — that the federal Fisheries Act infringes on their rights at an operational and legislative level. Madame Justice Garson found that many of the avenues for the federal Fisheries Minister to make unilateral decisions were flawed and unfounded. The ruling gave the parties two years to negotiate terms for how this would change.

As mentioned yesterday, the resounding silence from the federal government and Fisheries Minister following the decision — was impressive. The decision came down in early November 2009, not until the second week of February 2010 did the Fisheries Minister actually send a letter to the Nuu-chah-nulth (after multiple letters from Nuu-chah-nulth leadership); a letter that sounds like it was blathering nothingness suggesting the Fisheries ministry had not figured out how to move forward on the issue.

I am speculating here, but maybe it was because Fisheries Minister Shea was in early January promoting the seal industry, and with the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters because they are an “important stakeholder and partner with whom we currently work together on many initiatives relating to fish and fish habitat in Ontario” (yeah, Ontario a hotbed of salmon activity), and the various announcements in relation to Canada’s economic action plan.

In actuality, I think it is because there is so much shit in the fan at Fisheries and Oceans Canada these days that the air circulation for its 10,000 plus staff might be a little stagnant.

Fisheries and Oceans often find themselves with fecal matter flying towards the proverbial fan — it’s a darn difficult set of tasks, complex issues, and heated stakeholders and rights-holders involved in many aspects of the resources they are tasked to look after. In other words — they’re a big target. However, governing parties of the day have little long-term view. What’s the point? — especially in these days of minority governments.

Sadly, though the myopic or short-sighted view seems to be a plague upon the federal Ministry — that and the fact that they seem to lose good staff as if jumping from a sinking ocean-liner, and have an aging workforce that is set to cause attrition faster than avian flu in a Fraser Valley chicken farm. As, really, what’s the point of studying fisheries management these days and hoping for a lifetime career in a government ministry that’s about as seaworthy as a bathtub right now.

…

In February last year, the British Columbia Supreme Court issued a ruling in regards to the legislation that guides salmon farming in British Columbia: . Morton being the marine biologist who lives in the Broughton Archipelago between Vancouver Island and the mainland — where a significant concentration of salmon farms have developed over the last decade to two. Also plaintiffs in the case along with Ms. Morton were:

- the Wilderness Tourism Association,

- Area E Gillnetters Association, and

- Fishing Vessel Owners’ Association of BC.

The issue at hand was that Ms. Morton and other plaintiffs were claiming that the Province of British Columbia — specifically the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands — does not have the jurisdiction to manage finfish (salmon) aquaculture in B.C. waters.

See, in 1988, the federal government (Fisheries and Oceans) and the Province of BC concocted an agreement handing over management of salmon farms from Fisheries and Oceans to the Province. The Province of BC maintains that its “farming” and thus the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Agriculture.

Wrong!

This case had to go right back to the Constitution Act of 1867 (formerly known as the British North America Act). The Constitution Act divided powers between the Federal Parliament and Provincial governments with Sections 91 and 92. As Justice Hinkson said in his ruling for this case:

[107] The respective powers of Parliament and the provincial legislatures are set out in ss. 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867. Neither Parliament nor a provincial legislature can expand its jurisdiction over the classes of subjects in ss. 91 or 92 by passing legislation which purports to do so.

So the feds and province screwed up royally back in 1988 — basically they broke constitutional law from what I can see. The problem is that, as you may have read in posts over the last month to two, salmon farming has grown astronomically in BC waters since then — anywhere from 500-2000%. All of this guided by legislation that is not valid.

[193] … Given the specific enumeration of the management and protection of the fisheries in s. 91(12) of the Constitution Act, 1867, the national resource of the fisheries in not a matter that should or can be left to a level of government other than Parliament.

Justice Hinkson was left in a jam. He found the current provincial legislation invalid; and that the federal government had no legislation to guide salmon farming; it was:

[188]… constitutionally invalid…

[198] The absence of sufficient legislation to regulate fish farms could well be more harmful to the public than the perpetuation of the impugned legislation.

His only choice was to give the federal government a year to develop adequate legislation — meaning that it should have had this legislation since 1988. In the meantime, the status-quo would hold otherwise there would be no legislation (i.e. “more harmful to the public).

In a follow-up appeal process in January of this year, Justice Hinkson ruled that there would be a one-year ban on any new salmon farm licenses until the federal government (Fisheries and Oceans) could develop adequate legislation. The federal government didn’t even participate in the first court case.

(there are some other really curious aspects to this case surrounding “public” and “private” fisheries and the argument over what constitutes “standing” (e.g. see Cohen Commission and lack of definition — I’ll save these for another post, this one will already be long enough)

…

This instigated brown stained blades on the DFO fans… that was last spring.

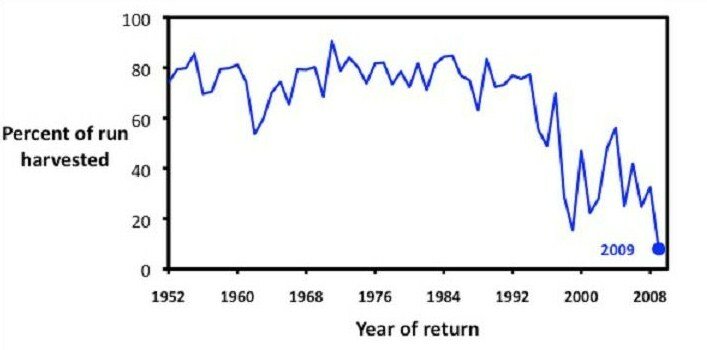

Then this summer the complete blown forecast on Fraser sockeye by Fisheries and Oceans. In early November, the Prime Minister’s office a public inquiry into the issue:

“The Government is establishing a public inquiry to take all feasible steps to identify the reasons for the decline of the Fraser River sockeye salmon population,” said the Prime Minister. “It is in the public interest to investigate this matter and determine the longer-term prospects for sockeye salmon stocks.”

I find some of this rather disturbing. On one hand it is good that a public inquiry has been a launched — however, how the hell is a Supreme Court Justice and a team of lawyers supposed to determine “the reasons for the decline”?

Isn’t that the job of Fisheries and Oceans? Isn’t that why they have an over $200 million budget for fisheries management and another $100 million or so for research?

The “longer term prospects”?

They’re not good Mr. P.M.

It has been determined that this year’s run was so small it won’t be able to produce a similar size run for the future. This is called a death-spiral….

Stockwell Day also informed us in the press release:

“This is a significant and important issue for BC fisheries industry,” said Minister Day. “Our government is deeply concerned about the low returns of sockeye salmon to the Fraser River and the implications for the fishery.”

Well, Mr. Day, granted you actually represent a BC constituency, I’m rather appalled.

There is no fishery. There has been no fishery for three years on Fraser sockeye. The “implications” are: No damn fishery for the foreseeable future. This isn’t a “significant issue” — this is a flippin disaster.

One individual in the BC interior – – has taken it upon herself to distribute canned salmon to impoverished interior First Nation communities (see ). Communities that have depended on the yearly return of salmon for thousands of years. Some estimates suggest that pre-European contact, First Nation individuals on the Fraser were consuming over 500 kg of salmon every year. Now that’s healthy.

Now, it’s 0 kg in many cases. There is no fishery. That’s devastating.

Unfortunately, the Terms of Reference for the public inquiry – the – are clearly laid out:

…conduct the Inquiry without seeking to find fault on the part of any individual, community or organization, and with the overall aim of respecting conservation of the sockeye salmon stock and encouraging broad cooperation among stakeholders.

There is one organization, and one organization only, tasked with making sure that wild salmon are well looked after. That organization is Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

If the Prime Minister says all “feasible steps”; is not one of those steps potentially the fact that Fisheries and Oceans dropped the ball? Not just dropped the ball, but utterly and completely mismanaged how the ball was even in the game in the first place… or was counting the wrong score; or plain and simply at the wrong game.

…

In the Nuu-chah-nulth case the Madam Justice had no problems “finding fault”.

In the Morton case, the Justice had no problem “finding fault” and suggesting it get fixed tout de suite.

There is a history of courts of law finding fault with the approach of Fisheries and Oceans Canada — as well as inquiries, Attorney Generals, and Royal Commissions. Some that in the 1990s were even officially called: “Here We go Again”.

…

The other day, March 2, federal Fisheries Minister Shea issued a quiet stating that all fisheries negotiations as part of treaty negotiations in British Columbia would be deferred until the Cohen Commission into the Fraser River sockeye declines is complete:

“The Government of Canada is deferring the negotiation of fisheries components at treaty tables in British Columbia that involve salmon, pending the findings and recommendations of the Commission of Inquiry into the Decline of Sockeye Salmon in the Fraser River. The deferral of fisheries related negotiations will allow for treaty negotiations to be staged so that fish chapters in treaties can be informed by the findings and recommendations of the Inquiry.”

I’m not sure if Minister Shea has looked at the geography of B.C. or of treaty negotiations. First off, I can’t imagine there isn’t anything more fundamental to treaty negotiations in most BC First Nation communities than fisheries. Secondly, not every Nation of the over 200 First Nations in BC is located on the Fraser River.

Why would the Gitsxan, or Tahltan, or Tsay Keh Dene be affected by the Commission’s ruling on Fraser sockeye? (Tsay Keh isn’t even in a Pacific drainage, it’s in the Arctic drainage.)

Even the Terms of Reference for Cohen Commission repeatedly state, for example:

B. …to consider the policies and practices of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (the “Department”) with respect to the sockeye salmon fishery in the Fraser River.

C. to investigate and make independent findings of fact regarding:

i. the causes for the decline of Fraser River sockeye salmon…

And really, if the Cohen Commission finds that the “current state of Fraser River sockeye salmon stocks and the long term projections for those stocks” is absolutely dismal — what would some communities have left to negotiate? (I understand there are other important components, however my experience has been fish are central)

Even the frames the fisheries issue as such:

Fishing Issues

Integral to First Nations’ Culture

First Nations have for thousands of years sustained vibrant and rich cultural identities profoundly linked to BC’s land and waters. It is said that the Nisga’a, people of the mighty river, are so connected to fish that their bones are made of salmon. Living in balance with the land and the water is an integral part of First Nations’ cultures, and fishing is regulated by longstanding cultural laws around conservation and preservation for future generations.

…

Justice Hinkson in the Morton case has a great observation:

[109] … the very functioning of Canada’s federal system must be continually be reassessed in light of the fundamental values it was designed to serve.

Sadly, it appears that the “fundamental values” of the federal fisheries system are lost. The complete destruction of North-Atlantic Cod was one of the first indicators.

That same federal system is arguing in courts of laws, denying in courts of law — the highest courts of the land — that coastal First Nation societies were not fish-based cultures, didn’t trade with other Nations, and have no commercial interests in fish or salmon.

It appears that maybe the “light” in the hallowed halls of the federal Fisheries ministry is being filtered through brown excrement… excrement that has been hitting fan blades and spraying across windows.

This is more than just shit hitting the fan. This is a full on shit storm.

In times of vastly shrinking public service budgets, red-numbered federal and provincial budgets, and court cases that are slapping a Ministry upside the head… the thought of a public inquiry headed by a judge starting to poke and prod into:

the policies and practices of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans with respect to the sockeye salmon fishery in the Fraser River – including the Department’s scientific advice, its fisheries policies and programs, its risk management strategies, its allocation of Departmental resources and its fisheries management practices and procedures, including monitoring, counting of stocks, forecasting and enforcement,

… has got to have some senior Fisheries bureaucrats seriously considering early retirement.

I will not be surprised to see an exodus from that Ministry faster than a cat hitting water. There is a fundamental shift afoot — and the shift is going to hit the fan real soon.

I might suggest that rather than carrying on this constant legal wrangling based on the act of ‘deny, deny, deny’ — why isn’t there a serious investigation into how First Nation societies up and down the Fraser River co-existed and co-managed salmon resources?

It was also done on the Columbia, the Yukon, the Stikine, and so on. Ground-breaking new approaches and management systems that actually work will not be coming out of bureaucratic behemoths.

Bureaucratic behemoths appear to need a serious slapping from the highest courts before they institute change — and even then, as demonstrated by Minister Shea’s silence on the Nuu-chah-nulth case… legal facts still don’t spur meaningful action.