In honor of the parade of theories on wild salmon, wild salmon declines, wild salmon inclines, salmon behavior and so on, and so on — I have added a new category to the blog “Theory Parade”.

Here’s one of the floats in that parade — the low food supply float. This float in the parade is decorated with a lack of phytoplankton, a lack of volcanic ash, and a lack of North Pacific Gyre — however there is some El Nino on one side of the float and some La Nina on the other side, driving the float is the Pacific decadal oscillation, on the rear are some squid and mackerel, and on the front is a beautiful sparkling dead zone of ocean acidification.

As you can probably guess… this is more of a float for Halloween then Christmas.

_ _ _ _ _

This headline out of the Vancouver Sun yesterday:

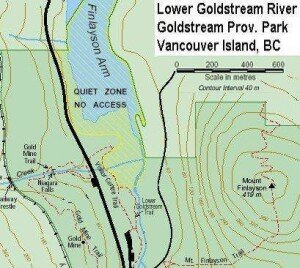

The theory here, in essence, that the chum from Goldstream (just north of Victoria, BC) went out to see in 2007 the same year that last year’s returning adult sockeye would have gone out as little gaffers.

Somehow between 2007 and 2008 — these theories (i.e. parade floats) suggest — the North Pacific shifted from a Saharan wasteland of salmon starvation to a Pacific Eden of dates of honey. Some suggest volcanic eruptions and ash deposited on the sea created a phytoplankton boom and thus the Pacific salmon Eden.

Further, thus, unless the Indonesian eruptions of late are depositing on the North Pacific, this year’s sockeye boom might only be a one off Thanksgiving Parade… we now return to a Saharan-like wasteland…

.

.

.

.

_ _ _ _ _

Returning to Goldstream for a moment… the un-mentioned in the article is the great cost at which Goldstream Creek has any salmon in it whatsoever. See it has, as far as I understand, at least three dams on it — largely for drinking water and what not. Yet, millions of dollars have been spent on the bottom last kilometre or so of the stream to “restore” salmon habitat.

Also, as far as I understand, it was never really a huge salmon producer historically.

About a decade or so ago I was on a ‘field visit’ to Goldstream as part of a “restoration”/”reclamation” conference. This was the time when millions upon millions of dollars was being poured into stream restoration and rehab; the time of the great Forest Renewal program; and other various slush funds.

There was some decent work done around BC at that time — however there were also some great gravy train — cash cow pet projects as well. One of them being Goldstream.

I asked the question, while touring the million dollar projects, is there a relation between the stream a mere miles from the urban Provincial capital and the amount of money being spent on a stream that will never be “restored” unless the dams are torn down…?

ohhh, the dirty looks — or “stink eye” as we call it around our house.

Sure, one could front the argument that the number of people that walk the trails of Goldstream, learning about salmon and habitat rehab, that this makes it all worth it…

It’s a similar argument that suggests that the “salmon in the classroom” project, whereby elementary kids raise salmon in classroom aquariums, is an excellent opportunity to teach about ecology, salmon life histories and so on. And, that when those kids release those baby salmon into the streams in buckets and then a few years later watch the adults return — is also a great learning opportunity.

However, is it also such a wise idea to teach our youth that the simple solution to ecology is technology?

Or, that to “restore” streams we simply need to get professional engineers involved and spend millions of dollars on heavy equipment and highly engineered habitat structures?

_ _ _ _ _

The real story around B.C. this year is that the bumper sockeye return to the Fraser River is largely an exception. Furthermore, that bumper is mainly just to the lower and lower-mid Fraser (e.g. the Adams River run probably comprises as much as 60-70% of the total Fraser sockeye return this year). There are no records up here in the Upper Fraser river for sockeye or any other salmon — or sturgeon for that fact.

About the only ‘record’ I’ve heard from other areas, is a good return of steelhead to the Skeena River — some theorizing that its because there was such a limited gillnet commercial fishery at the Skeena mouth this year (one of least species-selective methods of fishing).

Sure there were some decent salmon runs here and there — but when a stream such as Goldstream with its millions of dollars in human-made habitat structures and hatchery released chum, has a near record low run — or at least the bare minimum escapement to support the future (e.g. 4500 adults) — then we are far from out of the woods.

(worse yet, we sure as hell don’t have a breadcrumb trail like Hansel and Gretel to follow to get ourselves out of the deep dark woods).

_ _ _ _ _ _

somewhat more disturbing to me is statements such as this from the Vancouver Sun article:

Dick Beamish, senior scientist at the Department of Fisheries and Ocean’s Pacific Biological Station, said returns at Goldstream are below the numbers expected, but chum runs around the Strait of Georgia were expected to be down this year…… The good news is that, even if no more fish turn up, the 4,500 that have already spawned are enough to sustain the run.

“That is a sufficient number of fish to meet conservation goals for this year,” Beamish said.

No offence intended to Mr. Beamish — however its these sort of statements made with such certainty that may very well have got us into this position in the first place.

How can we be so sure that the “conservation goals” are being met… when we don’t even know what has caused the crash of so many salmon runs over the last decade?

How do we know that “conservation goals” are being met and that 4500 adult chum spawning in Goldstream is enough to ‘maintain’ the run when we have no idea what the baby salmon from these adults are going to have to face in the North Pacific (or Salish Sea for that fact) when they migrate out?

Well… the only thing we have is past knowledge. What has happened historically.

That’s great… but it’s only half the story.

In an age of such uncertainty — with things like climate change, shifting ocean currents, rapid ocean acidification, erupting volcanoes potentially fertilizing oceans, and the like — how can we run around making comments with such certainty that:

“The good news is that, even if no more fish turn up, the [whatever number] that have already spawned are enough to sustain the run.”

We just don’t know.

How do we, thus, then look after salmon in a time of such uncertainty and potential for rapid changes? Well… it’s called the precautionary approach.

With a whole lot of weight on the PRE and the CAUTION.

Meanwhile… the theory parade continues…